I have many copies of Tolkien’s works. It is a collector’s compulsion. But next to Tolkien I think the stories that I find have a similar depth are the writings of the poet whom we know as Homer. And I have four sets of translations of the Iliad and the Odyssey. The translations are by Fitzgerald, Robert Fagles, Peter Green and Emily Wilson.

I haven’t read Homer in the Greek. I was not smart enough to take Greek at school. That was for the scholarship students. But I enjoy the translations because they have their own magic and their own slant,

Fagles describes Odysseus as the man of twists and turns, Peter Green as that resourceful man and Emily Wilson as a complicated man. They all work to one level or another and I certainly prefer Odysseus to Achilles and the Odyssey to the Iliad. That said I think Fagles’ translation of the Iliad is the most graphic that I have read. The story jumps out of the pages and bronze age war is vividly and violently described and in detail. The Trojan War was a violent conflict.

So what has prompted me to write of Odysseus. It was an article in the New York Times by Daniel Mendelsohn who himself has published a new translation of The Odyssey. He noted that Odysseus was a sly hero with a penchant for guile, trickery and outright lies – the Odyssey an adventure story full of cannibalistic giants, seven-headed man-eating monsters and love-struck nymphs. But they are not tales of wonder from the ancient Mediterranean, although having sailed the wine dark sea and beheld rosy fingered dawn I am transported back. No, because Homer himself calls upon the Goddess:

“Now Goddess, child of Zeus,

Tell the old story for our modern times.

Find the beginning”

And that it is a tale for our modern times may explain its continuing popularity and continued retellings in other media. In 1954 there was a sword and sandals movie called Ulysses starring Kirk Douglas and in 1997 there was a miniseries – a brilliant absorbing telling – starring Armand Assante. (Part 1 is here. Part 2 is here)

Then this year there has been “The Return” directed by Uberto Pasolini and starring Ralph Fiennes and Juliette Binoche; and, expected next summer, an adaptation written and directed by Christopher Nolan, with Matt Damon as the “man of many turns,” as Mendelsohn calls Odysseus.

Those differing descriptions tell us of the hero’s multifaceted, multi-faced tricky, slippery self and it is perhaps this quality that today’s audiences and creators recognize, steeped as we are in debates about identities political, social, gendered and sexual in a world that, like that of Odysseus, often seems darkly confusing.

Mendelsohn suggests that the poem is a complex one about identity and that in a way is correct but it is more than that. True, Odysseus calls himself “No Man” when asked his name by the cyclops Polyphemus. After he blinds the cyclops the creature calls out to his concerned neighbours, “No man is hurting me,” so the neighbours leave him to his fate.

Throughout his adventures he alters his appearance until the end when, washed up on Ithaca, he takes on the guise of a beggar (aided by Athena) and is revealed only to a few until the bloody, brutal slaying of the suitors after he – the only one who could do it – bends the great bow and wreaks his vengeance against those who would have taken from him his world. The brilliant showdown in the 1997 retelling with the suitors can be seen starting in Part 2 from the link above at 1:19:00

This homecoming is critical. The Greek concept of nostos, or homecoming, lies at the core of The Odyssey. Odysseus' journey home from Troy is not merely geographical; it is existential and moral. His return to Ithaca is both a restoration of personal identity and a reassertion of rightful kingship.

The motif of identity—concealed, mistaken, or rediscovered—is threaded throughout The Odyssey. Odysseus is the "man of many ways" (polytropos), whose identity is elusive and multifaceted. His frequent use of disguises, especially upon his return to Ithaca, underscores the fragility and constructed nature of identity.

Notably, Odysseus’ recognition scenes—particularly those with Penelope, Telemachus, and the old nurse Eurycleia—are fraught with emotional and symbolic weight. These moments are not merely narrative pivots but revelations of internal truth and shared memory. Penelope’s final test of the bed, immovable and rooted, acts as a metaphor for the constancy of their bond and the restoration of Odysseus' true identity as husband and king.

The Odyssey is a myth of the return and Odysseus' trials—ranging from the seductive detours with Circe and Calypso to the Cyclops Polyphemus—symbolize the distractions and moral tests faced by any man seeking reintegration into society and family. His arrival home is thus a symbolic victory of order over chaos, a return not just to Ithaca but to himself.

But there are other critical themes. Xenia, the sacred code of hospitality, pervades the narrative, forming a moral framework through which characters are judged. Rooted in religious custom and social expectation, xenia reflects a reciprocal relationship between guest and host, overseen by Zeus Xenios.

The suitors’ abuse of xenia serves as a central justification for their destruction. Thus, the observance—or violation—of hospitality becomes a gauge of civilization and piety.

At the same time the Odyssey is a tale of endurance. Endurance (karteria), both physical and emotional, emerges as a heroic virtue in The Odyssey. Odysseus' patience and resilience are depicted as more essential to his success than martial prowess. While The Iliad extols kleos (glory) – golden-haired Achilles, son of Peleus knew all about kleos - through battlefield valor, The Odyssey emphasizes metis (cunning intelligence) and sophrosyne (self-restraint).

The tension between fate and free will also manifests in Odysseus’ decisions. Though aided by Athena and thwarted by Poseidon, he must still navigate the moral terrain of temptation, pride, and loyalty. The repeated refrain “endure, my heart, you have endured worse than this” (Book 20) encapsulates the internal strength required to fulfill his destiny.

And there are the Gods. Gods in The Odyssey are not remote arbiters of fate but active agents within the human realm. Athena champions Odysseus, guiding him home and ensuring justice is served. Conversely, Poseidon personifies the wrathful divine, punishing Odysseus for blinding his son, Polyphemus.

The epic upholds a theodicy in which justice, while delayed, is inevitable. The suitors’ fate, dispensed by Odysseus with divine sanction, restores moral order to Ithaca. This sense of cosmic balance, emphasized by the eventual reconciliation of the suitors’ families, suggests that the world of The Odyssey, though harsh, is governed by an intelligible moral order.

The interaction between Odysseus and the Gods in The Odyssey is central to the narrative and reflects the ancient Greek worldview in which mortals and immortals are intimately intertwined. The Gods are not distant deities but active participants in human affairs—protecting, punishing, guiding, or hindering according to their own motives, affections, and rivalries. Odysseus' journey home is shaped by his complex and often ambivalent relationships with these divine beings. This detailed analysis explores Odysseus’ major interactions with the gods, focusing on Athena, Poseidon, Zeus, Hermes, and lesser but significant deities such as Calypso and Circe.

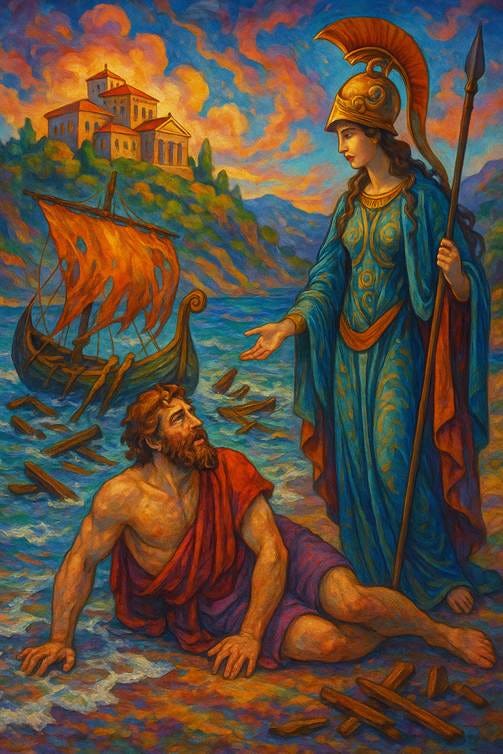

Athena, goddess of wisdom and war, is Odysseus’ principal divine ally. Her support is personal, consistent, and instrumental in securing his eventual homecoming. She often intervenes directly or through disguise to assist him and his son, Telemachus.

In Book 1, Athena pleads with Zeus on Odysseus’ behalf, urging him to allow the hero's return. She says:

“But my heart is broken for Odysseus, the seasoned veteran cursed by fate so long—far from his loved ones still, he suffers torments off on a wave-washed island...” (1.48–50, trans. Fagles)

This appeal sets the plot in motion and reveals Athena’s role as Odysseus’ advocate in the divine assembly.

Athena often operates in disguise, notably as Mentes and Mentor, guiding Telemachus in the first four books (the Telemachy). When Odysseus returns to Ithaca, it is Athena who disguises him as a beggar to protect him from premature recognition and to test others’ loyalty.

She orchestrates the reuniting of Odysseus and Telemachus and plays a crucial role in the final slaughter of the suitors. At the climax, she deflects arrows and gives Odysseus supernatural strength. However, she does not fight the battle for him; she empowers him to act, in keeping with Homeric ideals of heroism.

Athena’s support is both divine and pedagogical—she guides but expects Odysseus to use his metis (cunning). Athena and Odysseus are aligned in their strategic intelligence, making her the ideal divine counterpart.

On the other hand there is Poseidon, the God of the Sea serves as Odysseus’ primary divine adversary. His wrath is personal and persistent, stemming from the blinding of his son, the Cyclops Polyphemus.

“Poseidon... raged on, seething against the great Odysseus till he reached his native land.” (1.79–80)

This vendetta illustrates the peril of offending the gods. Odysseus’ taunt as he escapes the Cyclops

“Tell him Odysseus, raider of cities, took your eye!” (9.502)

betrays his pride (hubris) and provokes divine retribution. Poseidon’s revenge manifests as relentless storms and shipwrecks, making his enmity the principal obstacle to Odysseus’ return.

Unlike Athena, Poseidon rarely appears directly but influences events through the sea’s violence. His absence from Olympus in Book 1 (he is in Ethiopia) allows the gods to intervene on Odysseus’ behalf, a narrative device that opens the path for divine intercession.

Zeus, king of the gods, represents divine authority and balance. He does not consistently favor Odysseus but upholds the moral and cosmic order. When Athena pleads for Odysseus, Zeus agrees, signalling a shift in divine will:

“It’s not the will of fate that he should die there, far from his friends.” (1.81)

Zeus is often invoked in matters of justice and xenia. He punishes the suitors for their violation of hospitality and supports Odysseus’ return when Poseidon's wrath becomes excessive. However, Zeus also punishes Odysseus’ men for eating the sacred cattle of Helios, destroying their ship with a thunderbolt (Book 12), thereby reinforcing the idea that divine justice is inexorable.

Hermes plays a more limited but crucial role in The Odyssey. As the divine messenger, he is twice sent to alter the course of events:

In Book 5 Hermes instructs Calypso to release Odysseus. She protests the double standard applied to goddesses who love mortal men, but complies:

“You hard-hearted gods, you unrivaled lords of jealousy—scandalized when goddesses sleep with mortals...” (5.118–119)

In Book 10 when Odysseus’ men are transformed into swine, Hermes gives Odysseus the magical herb moly and advises him how to resist her magic. This act enables Odysseus to outwit Circe and gain her aid.

Hermes thus acts as a neutral facilitator between gods and mortals, helping ensure the divine plan proceeds.

Then there are the demi-Gods.

Odysseus’ encounters with the goddesses Calypso and Circe blur the line between threat and sanctuary. Each offers him comfort and immortality but at the cost of his identity and homecoming.

Calypso detains Odysseus on her island, Ogygia, for seven years. Though she loves him and offers immortality, Odysseus longs for Penelope and Ithaca:

“Nevertheless I long—I pine, all my days—to travel home and see the dawn of my return.” (5.219–221)

Calypso’s island symbolizes timeless temptation, but also stagnation. Her eventual compliance with Hermes’ command underscores that even powerful goddesses must submit to Zeus’ will.

Circe, the enchantress, initially threatens Odysseus by turning his men into pigs. With Hermes’ help, Odysseus resists her magic and becomes her lover. Unlike Calypso, Circe aids Odysseus after his resistance, advising him to seek Tiresias in the Underworld. This guidance is pivotal, showing that danger transformed through understanding can become wisdom.

In Book 11, Odysseus journeys to the Underworld, where he meets the prophet Tiresias, who provides critical information for his return. Though not a god, Tiresias speaks with divine authority, bridging the human and supernatural realms.

This episode emphasizes the theme of katabasis—a descent to the realm of death necessary for spiritual and narrative progression. It confirms the moral consequences of action (the punishment of the unfaithful) and the necessity of divine knowledge to fulfill fate.

Thus Odysseus' interactions with the gods in The Odyssey reveal a nuanced theology in which divine favor must be earned and maintained through humility, cleverness, and moral conduct. The gods do not negate human agency; rather, they frame its possibilities and limits. Athena empowers, Poseidon punishes, Zeus arbitrates, and others like Hermes and Circe mediate the boundaries between mortal and divine.

This complex interplay reflects the Homeric vision of a cosmos in which fate (moira), divine will, and human virtue are intricately connected. Odysseus survives not simply because he is favored by the gods, but because he embodies the qualities—resilience, intelligence, and self-restraint—that render him worthy of their support.

The Odyssey endures because its themes are not confined to Homeric Greece but speak to universal aspects of the human condition: the longing for home, the tension between disguise and identity, the test of endurance, the imperatives of justice, and the fragile yet vital framework of social norms.

Through the tale of Odysseus, Homer composes not merely an adventure, but a philosophical and ethical inquiry into what it means to live rightly in a world of suffering, wonder, and change.

Thank you Halfling, Stephen Fry has written “Odyssey” which is an easy and entertaining read of a hero’s way home

Go well. Steve

Thanks for this information, I've purchased the Fagles Odyssey and will keep the others in mind. And thanks for your pointers on the videos. The screen won't be huge but will have to do, and subtitles aren't a problem. I'll be looking out for those scenes you mention. I didn't see The Return and will keep it in mind for future viewing. I can't quite like Matt Damon for this next Odyssey go round, but let's see.

Wonderful to be planning a trip to Troy. I think if your son decides to throw down the spear he should do so in full costume!