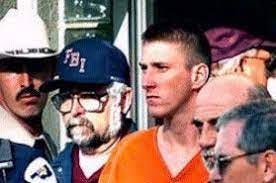

Homegrown: Timothy McVeigh and the Rise of Right-Wing Extremism - A Review

The arc between the Oklahoma City Bombing and the Capitol Riot of 6 January 2021

This is a book about the Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh. It traces an arc from the bombing on 19 April 1995 to the Capitol riots of 6 January 2021. Although the link is not obvious the author examines what drove McVeigh in the first place – if that can ever been clearly identified – and the rhetoric accompanying the Capitol riots.

There are some problems that author Jeffrey Toobin faces with his theory. The first is that McVeigh was a “lone wolf” although he did have an accomplice in the form of Terry Nichols. This image arose from the way that McVeigh’s trial was run.

The second is that with the advent of the Internet the events of 6 January became much easier to organize and coalesce. McVeigh did not have that. But Toobin is able to draw a number of parallels between some of McVeigh’s behaviour and interests and those of the Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers at the Capitol of 6 January.

Toobin structures his book not as a polemic but as a piece of legal journalism. The book is divided into two parts. The first part explores Timothy McVeigh, who he was, his background, his lifestyle and his gradual descent into the abyss that was the Oklahoma City bombing. The second part deals with the trial and examines the players, the trial strategies of the prosecution and the defence and the conduct of the trial leading up to McVeigh’s sentencing and execution. It is in the epilogue that Toobin attempts to draw the threads together with mixed levels of success.

The first part traces McVeigh’s early family life. Toobin describes an arrogant, lonely kid who constantly deflected responsibility, loath to own up to his failures. Then he joined the military. He was a brilliant marksman who fought in the first Iraq war but failed a tryout for the Green Berets after only two days. This, Toobin writes, was “a shattering defeat … he had no plan B”. By the time he met Nichols during basic training in 1988, McVeigh had already found the two things that would provoke in him a fanatical devotion – a books and guns.

McVeigh’s ideological development rested in his reading of right-wing lieterature. Important influences were Spotlight and Soldier of Fortune magazines which McVeigh consumed avidly along with a novel, The Turner Diaries, which envisaged a world in which the government had the power to confiscate private arms, Black people were allowed to attack whites with impunity and whites were punished for defending themselves. It also imagined the blowing up of the FBI building in Washington with a truck filled with thousands of pounds of fertilizer, blasting gelatin and sticks of dynamite. This became the model for McVeigh’s bombing of the Alfred P Murrah Building in Oklahoma City. What McVeigh hoped was that the bombing would be the start of a revolutionary rising – which never happened.

The Turner Diaries inspired a number of other terrorist attacks in both the United States, the UK and Germany. The books was removed from Amazon and its subsidiary platforms and has been banned in Germany since 2006. In Canada, The Turner Diaries is one of many titles considered by the Government of Canada to be "obscene" and "hate propaganda" under the Criminal Code. A search of the Classification Office in New Zealand indicates that the title is not considered objectionable.

There were other factors that came into play. McVeigh was galvanized by the standoff at Ruby Ridge in 1992 and the fiery, deadly end of the 51-day standoff between the F.B.I. and David Koresh at his Branch Davidian compound near Waco on 19 April 1993. It was no accident that McVeigh planned his bombing for the anniversary of that latter event.

McVeigh was also a supporter of the right to bear arms guaranteed by the Second Amendment to the US Constitution and was infuriated when the Government under President Clinton banned assault weapons. But this does not explain the level of visceral anger that must have been necessary to undertake the bombing and although Toobin provides a detailed context, the deeper motivation does not become clear.

McVeigh would go on to become a regular at gun shows, eventually cajoling Nichols into robbing a dealer so that they could fund their bombing plot.

In reading the book I was not convinced that McVeigh’s actions were anything other than those of a lone wolf. Some commentators have referred to McVeigh’s characterization of his actions as a military action and that he attended militia meetings. The view is that McVeigh wasn’t just some lone-wolf drifter or survivalist oddball. He was steeped in an ideology and was motivated by a political movement. Yet despite his connections with some militias, none of them followed him and in fact the Michigan Militia condemned the bombing.

The second part of the book details the trial and from Toobin’s perspective – and he covered the legal proceedings for the New Yorker – part of the reason why McVeigh’s motivations and his ideological drivers did not become clear lay in the way that the Government prosecuted the case. The Justice Department lawyer, Merrick Garland (who is now President Biden’s Attorney-General) was so intent on pruning away anything resembling “clutter” that “the idea took hold that the bombing was just about Tim McVeigh and Terry Nichols, McVeigh’s co-conspirator.

Vowing that the Oklahoma City trials would never devolve into silly theatrics – like the contemporaneous O J Simpson trial - Garland wanted the case to hew as closely to McVeigh and Nichols as possible. So the prosecution “actively discouraged the idea that McVeigh and Nichols represented something broader — and more enduring — than just their own malevolent behavior,” Toobin writes. “This was a dangerously misleading impression.” Despite that, Toobin concedes that The US of the 1990’s was a different place. The radical right was on the fringe - too extreme, too weird, too atomized to coalesce into anything that could get its hands on actual power. Social media didn’t exist.

Notwithstanding, Toobin goes to some pains to draw what is promised as a “direct line” between the Oklahoma City bombing and the insurrection on Jan. 6; at multiple points Toobin interrupts his brisk narrative with some heavy-handed reminders to the reader of parallels that he claims are glaringly obvious.

The lead-up to the trial is well-handled. McVeigh’s case was not heard in Oklahoma. It was considered that it was unlikely that he would get a fair trial. The Judge to whom the trial was assigned appointed publicly funded lawyers to act as McVeigh’s defence and Toobin is able to offer penetrating insights into the lead-up to the trial and the difficulties that the defence had with a client who was candid in his involvement but nevertheless sought an acquittal. Much of this information came from 635 boxes of case files donated by Stephen Jones, McVeigh’s showboating lawyer to the University of Texas in 1999. Toobin describes how the lawyer and his client grew to dislike and mistrust each other. After McVeigh criticized Jones in “American Terrorist,” a book by two Buffalo News reporters, Jones claimed “a right to defend himself by disclosing his client’s confidences.” Toobin gives credit to “American Terrorist” as a guide to McVeigh’s life and the access to the correspondence that the authors had with McVeigh.

Toobin negotiates the minefield of what at first blush amounts to an egregious breach of lawyer\client privilege which continues even after the death of the client. Toobin not only examines the justification for the disclosure of the material but also his own use of it. Stephen Jones had no authorization from McVeigh to release the materials but was concerned at the impression of his abilities that was created in “American Terrorist”. His justification in defending himself was rejected by Toobin. But Jones also suggested that, in the words of Justice Felix Frankfurter, that history had its claims and Toobin suggests that in his book he tried to make it.

Apart from the occasional side-comments that interrupt the narrative, Toobin develops the link between McVeigh and the far-right extremism that manifested itself on 6 January 2021 and deals with this in the final chapter to the book. He considers the birth of the extreme language that now dominates Republican politics. McVeigh embraced white supremacy and violent action just as a Republican House speaker, Newt Gingrich, and a talk show host, Rush Limbaugh, were engaging in “rhetorical violence at a pitch the country had rarely heard before on national broadcasts”.

In addition there was the extreme position adopted by Pat Buchanan who was challenging George H W Bush for the Presidency. According to Sean Wilentiz writing in the New York Review of Books it was

“from Buchanan, McVeigh learned of the menacing New World Order(NWO), purportedly a project of shadowy, powerful, internationalist elites to topple the America created by the Founding Fathers and replace it with a single omnipotent world government run exclusively by and for themselves. From Buchanan, he learned that a new revolutionary resistance could defeat the NOW much as the patriots of1776 had defeated the British.

And from Buchanan, perhaps most important of all, he learned that, just as the redcoats had once tried to strip the patriots of their arsenals, so the nefarious globalists and their liberal minions were out to shred the Founders’ Second Amendment and seize the guns of a God-fearing citizenry. For Buchanan, Toobin writes, “guns meant freedom.” McVeigh already believed as much, but Buchanan politicized that belief as never before.”

Thus for Toobin McVeigh was superficially a lone terrorist who found a kind of community in right-wing periodicals, talk radio call-ins, and farflung gun shows, the Internet and social media have at once vastly enlarged that community and tightened its connections, with billions of unfiltered rants and orders and falsehoods flashing through the ether. McVeigh thought it would take a grandiose act of targeted terrorto arouse what he only sensed was an immense army of like-minded militant patriots. Today’s extremists know with certainty that the army exists and for Toobin that was demonstrated on 6 January 2021 and he details the various attacks and massacres that have taken place since the 1995 bombing, scribing the arc of violence that has characterized American life ever since. Not all of these acts can be characterized as examples of right-wing extremism but they draw upon the terror that they create. Toobin suggests that to label such attacks as lone wolf exploits minimizes the threat posed even although they were not part of larger conspiracies.

It is in the emergence of Trump that Toobin suggests that the wolves had a new leader. Trump used the language of violence using inference and innuendo. He was aggressive and confrontational throughout his presidency and continues so. Jennifer Szalai writing in the New York Times perhaps completes the arc that Toobin drew in “Homegrown” when she wrote:

“It was the dog whistle heard ’round the world. When Donald J. Trump decided to kick off his latest presidential campaign on March 25 with a rally at Waco, Texas, he was issuing a call to the far-right fringe that was earsplitting, even by his own standards. It wasn’t simply the location but also the timing: a month shy of the 30th anniversary of April 19, 1993 — a date that marked the fiery, deadly end of the 51-day standoff between the F.B.I. and David Koresh at his Branch Davidian compound near Waco.

Along with the standoff at Ruby Ridge , in 1992, Waco became a galvanizing moment for the radical right. Exactly two years later, on the morning of April 19, 1995 , Timothy McVeigh drove a Ryder truck loaded with a 7,000-pound fertilizer bomb to the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City. He lit the fuse, parked the truck and walked to his getaway car in a nearby alley. The blast sheared off the front third of the building, killing 167 people, 19 of them children. (Another victim, a rescue worker, was killed by falling debris.) Among the dead were 15 preschoolers who had just started their morning at the day care center on the second floor.”

Trump has no filters – we all know that. But the start of his bid connects to the motivators for McVeigh, fanning the embers of hate that accompany those motivators. Toobin’s book provides some interesting and concerning signposts to explain where America is at now.