Hot on the heels of the International Mastermind competition in Sydney my wife and I were able to enjoy our all expenses paid trip to the UK and Europe departing at the end of June 1981.

Our trip involved two weeks in London, two weeks travelling in Britain and two weeks on the Continent – France, Italy and Germany – before returning home a couple of days after the wedding of Prince Charles to Princess Diana.

On the first leg we were put up in a hotel named the Royal National in Russell Square. At the time it is what I would describe as a tourist hotel. It was all pretty basic and certainly no frills. It was comfortable and a tube station (Russell Square) was located nearby.

There was also a nearby pub on the way to the station called The Friend at Hand (which is still there) which became a regular stopping point after a day in London seeing the sights.

A short walk from the Royal National (down Bedford Way, across Russell Square and down Montague Street to Great Russell Street) was the wonderful British Museum. We made a couple of visits to that amazing place. At the time the British Library was on the same premises (it has since moved to Euston).

One late afternoon I paid a solo visit to the Museum. There was an exhibition on the Celts that I wanted to see and I emerged from the Museum at about 4:30 pm. Opposite the main gates leading in to the Museum was a street aptly named Museum Street and I could see a number of antiquarian bookshops down the street.

Yielding to the temptation to go and have a look, down Museum Street I went, feasting my eyes on window displays of not only antiquarian books but antiques as well. It was all very fascinating and as I turned to head back up Museum Street to walk back to the hotel, I saw a window display of Tolkien books. Clearly a place that deserved a look but in fact it was the display window of the publishers George Allen and Unwin. The building at 40 Museum Street was named Ruskin House and the history of the publishers explains why.

Ruskin House today

Diversion 1 – George Allen and Unwin

George Allen & Unwin was a British publishing company formed in 1911 when Sir Stanley Unwin purchased a controlling interest in George Allen & Co. It became one of the leading publishers of the twentieth century and to established an Australian subsidiary in 1976.

George Allen & Sons was established in 1871 by George Allen, with the backing of John Ruskin, becoming George Allen & Co. Ltd. In 1911 when it merged with Swan Sonnenschein and then George Allen & Unwin on 4 August 1914 as a result of Stanley Unwin's purchase of a controlling interest.

Frank Arthur Mumby and Frances Helena Swan Stallybrass, Unwin's son Rayner S. Unwin and his nephew Philip helped him to run the company, which published works by Bertrand Russell, Arthur Waley, Roald Dahl, Lancelot Hogben and Thor Heyerdahl.

It became well known as J. R. R. Tolkien's publisher some time after publishing the popular children's fantasy novel The Hobbit in 1937, and its high fantasy sequel The Lord of the Rings novel in 1954–1955. Book series published by the firm in this period include the Muirhead Library of Philosophy and Unwin Books, a paperback imprint.

Allen & Unwin's major problem, acute in the mid-1980s, was being middle-sized, neither large enough to absorb overheads easily nor small enough to be quirky and buoyant. The company showed its first loss in 1985 and 1986 the firm was amalgamated with Bell & Hyman to form Unwin Hyman Ltd., with Robin Hyman as chief executive. From this time "Allen & Unwin" continued only as the name of the Australian subsidiary of Unwin Hyman.

In 1990 Hyman sold the firm to HarperCollins. The new owners retained in print no more than a few highlights, such as the Tolkien books, and only employed half a dozen members of the Unwin Hyman staff.

The asset-stripping operation, as Rayner wrote (in a privately published book called A Remembrance) was "messy, depressing, and, at times, outrageous for those at the receiving end". HarperCollins has since sold Unwin Hyman's academic book list to Routledge of which more later.

Back to Museum Street

In some respects I had reached what, for devoted Tolkien readers was a scared site. I cannot recall what motivated me to do what I did next. I can only speculate that within my own experience I had an expertise in Tolkien that could not go unnoticed and so I walked into the reception area of the building and asked if it might be possible to speak with Mr. Rayner Unwin.

In retrospect to do that took a degree of chutzpah and quite a bit of nerve, but when I was asked for my name, which I gave, I was told that Mr Unwin had been trying to get in touch with me and a moment or two later a tall, distinguished gentleman came down the stairs and introduced himself. This was Rayner Unwin whose review of “The Hobbit” at the age of 10 started the whole Tolkien publishing behemoth.

The review reads as follows:

"Bilbo Baggins was a Hobbit who lived in his Hobbit hole and never went for adventures, at last Gandalf the wizard and his Dwarves persuaded him to go. He had a very ex[c]iting time fighting goblins and wargs. At last they got to the lonely mountain; Smaug, the dragon who guards it is killed and after a terrific battle with the goblins he returned home – rich!

This book, with the help of maps, does not need any illustrations it is good and should appeal to all children between the ages of 5 and 9."

Unwin was absolutely charming and gracious. Introductions and an initial exchange was followed by an invitation up to his office for a glass of wine and a chat. It was, as Tolkien would have it, a merry meeting.

Unwin was ecstatic that the Mastermind exposure had brought Lord of the Rings to the forefront of public consciousness and we spoke of that. He opened a filing cabinet which contained correspondence with Tolkien – an opportunity to touch the paper that had been touched by Tolkien. We agreed to meet a couple of days later for lunch.

Lunch was a joy. Unwin was a great walker and had trekked in many exotic locations. So we walked to a restaurant on the Tottenham Court Road. This was a walk through Bloomsbury and Unwin gave me a literary tour of this writers’ haven – here was where Virginia Woolf lived, there, E.M Forster, Lytton Strachey, Roger Fry and others. It was a fascinating walk, topped off with a lovely luncheon at a restaurant that was patronized by a number of writers including, as I recall particularly, Harold Pinter whose plays I had studied at University.

We parted company after a brief suggestion by Unwin that perhaps I should think about writing a book about Tolkien and the Lord of the Rings. The angle was that I was in control of the facts. Now for an interpretation. I promised to give it some thought.

In 1982 Unwin visited Auckland and we went to dinner at what was The White Heron in Parnell. My wife, who had not read Lord of the Rings was told by Unwin that Mrs Tolkien hadn’t read it either, so it was no big thing. But once again Unwin reiterated that I should think about writing a book about the Lord of the Rings and Tolkien’s writing. We had discussed some of the angles that such a book should take and so it was in later 1982 and early 1983 I bought an IBM Selectric typewriter, taught myself to type and got started. The resulting manuscript – a copy of which I still have – was given a working title of “A Prospect of the Mind” (which came from a line in Wordsworth’s “Prelude”)

The manuscript was sent to Rayner Unwin in May of 1983.

Dealing with Rayner Unwin was a real joy and his knowledge and connections were wonderfully helpful for someone who was starting out with a “first book” that was admittedly very ambitious. So who was this lovely, helpful man?

Diversion 2 – Rayner Unwin

Unwin was born in 1925 in Hampstead, London, one of four children from the marriage of publisher Stanley Unwin and Mary née Storr (1883–1971).[3] His father was the founder of the publishing house George Allen & Unwin.[3] As a young boy, Unwin served as a test reader for the firm, as his father believed that children were the best judges of what made good children's books. He was paid one shilling for each written report, which as Unwin later remarked was "good money in those days".

Most notable among the reviews he wrote for his father was his 1936 report, aged 10, for the J. R. R. Tolkien book The Hobbit. "Not a very good piece of literary criticism," he later said of the report, "but in those happy days, no second opinion was needed; if I said it was good enough to publish, it was published."

After attending Abbotsholme School in Rocester between the ages of 10 and 17, Unwin started working as a book salesman for Basil Blackwell, whose father was the founder of Blackwell's bookshop in Oxford. Between 1944 and 1947, he served in East Asia as a sub-lieutenant in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. He then studied for an undergraduate degree at Trinity College, Oxford, before completing a master's degree in English at Harvard University, which he attended as a Fulbright scholar.

In 1951, Unwin began working for his father's firm George Allen & Unwin, with a starting salary of £34 per week. His obituary in the Guardian noted:

“It cannot have been easy working there, on £34 a week. His father read all the mail, both incoming and outgoing. The place was Dickensian, its ledgers and orders written by hand. Employees complained of bed bugs, left over from the building's wartime use as a public air raid shelter. The offices, never elegant, became yet more labyrinthine after numbers 40A and 41 were purchased.”

The publishing house had some notable authors including Lancelot Hogben, Bertrand Russell, Julian Huxley and then, most amazingly of all, Thor Heyerdahl, after Stanley's nephew, Philip Unwin, stumbled upon the Kon-Tiki story while visiting Scandinavia.

Rayner Unwin was offered the manuscript for The Lord of the Rings. He thought it ought to be published as well, and writing to his father with the figures, he said he thought they might lose a thousand pounds. Sir Stanley wrote back, saying "If you think this to be a work of genius, then you may lose a thousand pounds."

Unwin was also responsible for the first UK publication of the Roald Dahl children's books James and the Giant Peach and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Dahl had been struggling to find a publisher for these titles in the UK, but caught the attention of Unwin after Unwin's daughter Camilla became captivated by a copy of James and the Giant Peach that her schoolfriend Tessa Dahl (Roald's daughter) had given her.

When Sir Stanley died in 1968, Unwin became the new chairman of the firm. His father had been preparing him for the role during his time at the firm; Rayner's older brother David had decided to pursue a career as a children's author instead. David Unwin later wrote in his memoirs: "I have always felt guilty at my defection, for by taking my place Rayner sacrificed his own promising career as an author".

Initially, the firm enjoyed success under the chairmanship of Unwin. However, during the 1980s, the firm's comparatively small turnover of £8 million became a cause for concern. As noted above in 1986, George Allen & Unwin was merged with Bell and Hyman to form Unwin Hyman, with Unwin acting as chairman. In 1989, the new firm faced serious difficulties when managing director Robin Hyman became seriously ill at a time when the company's profits were declining rapidly.

The company was acquired by HarperCollins in 1990, a decision to which Unwin was opposed. Before the contract was signed, Unwin resigned as a protest,and he remarked to his friends: "I feel I've betrayed my father."

Unwin was also the writer or editor of several works, which were published in two periods. His first period of writing activity came during his first decade at Allen & Unwin.

Unwin was awarded the CBE in 1977, was a senior figure with the Publishers Association, notably for the 23rd International Publishers Association Congress of 1987, the first to be held in the UK since 1936, when his father had been in charge.

He was the editor of The Gulf of Years: Letters from John Ruskin to Kathleen Olander (1953). He produced a critical work on poetry entitled The Rural Muse (1954), which covered the work of poets such as John Clare, George Crabbe and Stephen Duck. This was followed by The Defeat of John Hawkins: A Biography of His Third Voyage (1960), a detailed account of the expedition made by 16th-century navigator John Hawkins to San Juan de Ulúa in Mexico. Initially published by George Allen & Unwin, it was later reissued by Pelican.

Late in his life, Rayner wrote A Winter Away From Home (1995), a young-adult history book about Dutch explorer William Barents and his 16th-century voyages to the Arctic.

Unwin married Carol Margaret née Curwen (1924–2012) on 3 April 1952. Carol's father Harold also worked in the publishing trade, as the owner of the Curwen Press. The two families had known each other for a long time, as Stanley Unwin and Harold Curwen had attended Abbotsholme School together. Carol Curwen was working as a nurse at the time of their marriage.

Their first married home was a flat above the Museum Street offices of Allen & Unwin. They later moved to Limes Cottage, a Grade II listed property in the Buckinghamshire village of Little Missenden. They continued to live there until their deaths, in 2000 and 2012 respectively. Unwin served as chairman for the annual Little Missenden Music Festival between 1981 and 1988.

The Unwins had four children: three daughters and one son. His son Merlin also entered the publishing trade, initially working for George Allen & Unwin before setting up his own independent publishing company, Merlin Unwin Books, with a focus on countryside and fishing.

Unwin was a member of the Garrick Club and died of cancer on 23 November 2000 at the Hospice of St Francis in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire. His cremated remains were taken by his daughter to the Himalayas, a favourite walking place, and scattered there.

Back to 1983.

In July 1983 I received a letter from Unwin. The delay in responding to mine of May 1983 had been occasioned by him having sent the manuscript to Christoper Tolkien and Unwin stated:

“I am happy to say that his view coincided very much with mine – that it is an entirely excellent study that you have created, approached it from the right angle, that is through THE SILMARILLION, and what you say is entirely sensible. In short, though studies about Tolkien are subject to almost a conspiracy of silence these days in the reviewing media and in consequence do not produce great sales figures we would nonetheless like to see your book published.”

But a lot of work needed to be done on the manuscript as Unwin went on to say, commenting on the style:

“..it is very stiff in its presentation, almost as though you were presenting a thesis to an examiner. I just wonder if you ought not to look at it again before we put it to press and, perhaps in the knowledge that it can be published, you would consider your reader a little more humanely and relax a bit in the exposition.”

He was, of course, quite right. I sometimes wonder if I have managed to be a bit more flexible and readable in my style, even now 41 years after that critique. Dropping the “legal style” for both opinions and judgements involves quite a bit of rewiring.

By October 1983 I had reworked five of the chapters and redrafted three others and sent the revised manuscript off with some suggestions for titles. “A Prospect of the Mind” was a bit vague and I thought that a focus on the fact that it was a book about Tolkien’s writings would attract more interest.

One title we considered was “A Mythology for England” but that had been used as a subtitle by another author. That became the title of the final revision which was completed in December 1983. But the title was something of an issue and it was not until August 1984, with the help of David Fielder at Allen & Unwin who was handling the book, we settled on a new title.

Professor Tom Shippey had written a book (published by Allen & Unwin) entitled “The Road to Middle-earth” which has since been reissued revised and expanded with a previously unpublished lengthy analysis of Peter Jackson's film adaptations and their effect on Tolkien's work.

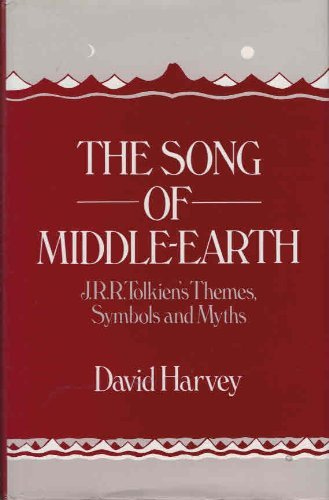

Because my book was an analysis of the themes, symbols and myths present in the Tolkien “canon”, which at that stage was “The Hobbit”, “The Lord of the Rings” and “The Silmarillion” I though I might continue the main title theme present in Shippey’s work and call mine “The Song of Middle-earth: J.R.R. Tolkien’s Themes, Symbols and Myths”.

Production commenced in September 1984 and the page proofs were sent in October 1984 with instructions on how to make amendment along with some detail about putting together an index and the work was completed in November 1984. In January 1985 further excitement when the colour proofs for the dust-jacket arrived and the book was finally released in March 1986.

Diversion 3 – Dragon Smoke

While the The Song of Middle-earth” was going through its lengthy gestation period I was asked by Allen & Unwin’s representatives here in New Zealand if there was any other material that I had that might be published.

As it happened I did – a number of short children’s stories that I had written for my daughter explaining the background and “history” or “mythological origins” for gifts given – an in particular a soft-toy dragon. To build a reasonable collection for publication I wrote a number of other tales which included familiar objects in out lives, including our Great Dane dog who sadly departed in 1985 and whose apotheoisis formed the basis of one of the tales.

Allen & Unwin’s Australian arm was responsible for the publication of the book which was titled Dragon Smoke and Magic Song.

One thing needed attention and that was illustrations. Given my continued correspondence with Rayner Unwin I suggested to him that I would like Pauline Baynes to illustrate, if she was interested.

Pauline Baynes was an English illustrator, author, and commercial artist. She contributed drawings and paintings to more than 200 books, mostly in the children's genre.

She was the first illustrator of some of J. R. R. Tolkien's minor works, including Farmer Giles of Ham, Smith of Wootton Major, and The Adventures of Tom Bombadil. She became well-known for her cover illustrations for The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, and for her poster map with inset illustrations, A Map of Middle-earth. She illustrated all seven volumes of C. S. Lewis's Chronicles of Narnia, from the first book, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. Gaining a reputation as the "Narnia artist", she illustrated spinoffs like Brian Sibley's The Land of Narnia. In addition to work for other authors, including illustrating Roger Lancelyn Green's The Tales of Troy and Iona and Peter Opie's books of nursery rhymes, Baynes created some 600 illustrations for Grant Uden's A Dictionary of Chivalry, for which she won the Kate Greenaway Medal. Late in her life she began to write and illustrate her own books, with animal or Biblical themes.

It was cheeky I know, but it paid off in that Unwin was able to secure Pauline as illustrator and a very pleasant correspondence took place between author and artist and the illustrations Pauline created were magnificent.

As it happened Dragon Smoke was published before The Sone of Middle-earth and so takes the laurel as my first published book even although The Song was still in gestation.

Fast Forward to 2015

Both books did reasonably well but did not appear in the best seller lists. Indeed over the years the royalty statements for the Song became less and and less frequent and the book went out of print. Occasional copies appeared on the second-hand market, selling for substantially more than the original price. Because our copyright laws do not have droit du suite where an artist (or author) “clips the ticket” on a resale, the sellers of these second hand copies took all the benefit.

Then out of the blue in April 2015 I received an email from Routledge. It will be remembered that when HarperCollins took over Unwin Hyman Routledge took over their academic catalogue.

The enquiry was about whether the rights had reverted to me because Routledge were interested in issuing a new edition.

The issue of rights was a complicated one and on the face of the contract was not immediately clear. There was a lengthy exchange of emails with Routledge and with HarperCollins as to the state of the play. By August 2015 it was clear that HarperCollins as successors to Allen & Unwin wanted to retain the rights and were contemplating a reissue of The Song. This entailed signing a fresh contract because what was signed in 1984 did not contemplate electronic editions or the way the publishing market had changed. There was also a small delay because HarperCollins wanted to get Christopher Tolkien’s approval to the reissue.

Routledge were very reasonable although disappointed at the outcome, but recognized that a contract is a contract. But it may be that their interest sparked a renewal of interest by HarperCollins.

The reissued Song came out in 2016 with a new dustjacket that had a different colour scheme but retained the essential theme of the earlier cover.

In addition The Song is available in paperback and e-copy as well as in hard back although I understand that hard back copies are specially printed. Because of the way the publishing business works these days, although hard cover copies are “bespoke” the price is reasonable.

The royalty statements arrive every six months and the astonishing thing is that The Song is doing better in its resurrected iteration than it did when first published.

Reflections

I have no plans to update The Song or prepare a new edition. Everything that appeared in the book when it was first written says what I wanted to say and I haven’t had cause to rethink it.

Christopher Tolkien’s magisterial editing of Tolkien’s creative path, published in the 12 volume series The History of Middle-earth charts the creative path of J.R.R. Tolkien’s mythology and probably is indicative of the way that mythological tales develop. But The Song focused upon the books that Tolkien had authorized for publication (although The Silmarillion was unfinished at his death) and I felt it better to restrict my ambit to the Canon (in the same way that there is a “canon” of Sherlock Holmes stories notwithstanding volumes of “pastiche” stories by authors other than Conan Doyle.

When I wrote The Song the book Unfinished Tales had been issued. In some respects this was a precursor to The History but I could not find anything in Unfinished Tales nor in The Book of Lost Tales (Volume 1 of The History which was published while I was preparing the page proofs) that departed from the thematic or symbolic treatment that I was examining in The Song.

My interest in Tolkien continues. It is a joy that his work has become part of mainstream 20th Century literature and that there has been a considerable number of academic studies done on his work. I treasure particularly the amazing work done by Wayne Hammond and Christina Scull who have contributed mightily to Tolkien Scholarship and whose books The Lord of the Rings – A Readers Companion and The J.R.R. Tolkien Companion and Guide are essential for any Tolkien Library.

There is a continuing stream of publications and re-publications of Tolkien’s work. HarperCollins has just released a three volume collection of Tolkien’s Collected Poems edited by Hammond and Scull. But there is one poem Tolkien wrote that is in its own volume. It served as the inspiration for the end of the final chapter in The Song and reflects the closing paragraphs of The Return of the King.

“…and the sails were drawn up, and the wind blew, and slowly the ship slipped away down the long grey firth; and the light of the glass of Galadriel that Frodo bore glimmered and was lost. And the ship went into the High Sea and passed on into the West, until at last on a night of rain Frodo smelled a sweet fragrance on the air and heard the sound of signing that came over the water. And it seemed to him that as in his dream in the house of Bombadil, the grey rain-curtain turned all to silver glass and was rolled back, and he beheld white shores and beyond them a far green country under a swift sunrise”

The poem is Bilbo’s Last Song (At the Grey Havens) and I have heard it read at funerals.

Day is ended, dim my eyes,

but journey long before me lies.

Farewell, friends! I hear the call.

The ship's beside the stony wall.

Foam is white and waves are grey;

beyond the sunset leads my way.

Foam is salt, the wind is free;

I hear the rising of the Sea.

Farewell, friends! The sails are set,

the wind is east, the moorings fret.

Shadows long before me lie,

beneath the ever-bending sky,

but islands lie behind the Sun

that I shall raise ere all is done;

lands there are to west of West,

where night is quiet and sleep is rest.

Guided by the Lonely Star,

beyond the utmost harbour-bar

I'll find the havens fair and free,

and beaches of the Starlit Sea.

Ship, my ship! I seek the West,

and fields and mountains ever blest.

Farewell to Middle-Earth at last.

I see the Star above your mast!

The poster is by Pauline Baynes

The final reflection in this series is the story of how I arrived at the series title Journeys in Middle-earth.

In 2023 we went on a cruise from Miami to Lima, Peru. Before we disembarked we had an opportunity for a shore excursion and we took a bus from the wharf to the suburb of Miraflores, a residential and upscale shopping district. We went to a shopping centre that hung off the side of a cliff called Lacomar.

This was quite a remarkable centre that had a wide range of shops including a bookshop named Ibero Librerias (Ibero Bookstores). There are 12 bookstores in the chain located throughout Lima.

The Lacomar shop is beautifully designed and a pleasure to visit. Of course most of the titles are in Spanish but there is an international section as well as a well-stocked Tolkien section.

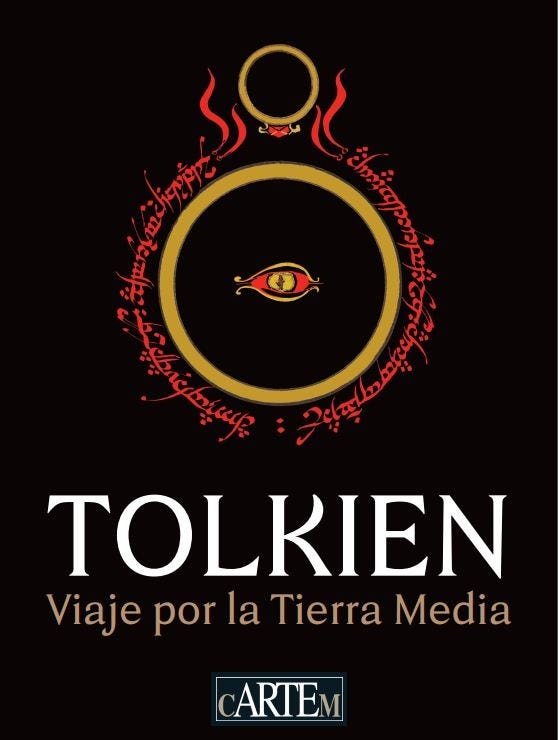

It was there that I came across a published catalogue for a Tolkien exhibition that was originally at the Bibliotheque National in Paris. In keeping with many such exhibitions the catalogue is not only a souvenir but often a work of scholarship and this catalogue is no exception

The title is A Journey Through Middle Earth which I have taken and adapted as the title for this series – Journeys in Middle-earth.

I hope you have enjoyed my meanderings

Wow, this was so interesting and moving. How enriched your life has been by Tolkien's great works - and you have contributed to the treasure that is his legacy. I read The Hobbit and LOTR to my children. I've always felt that the literature of mythology touches something deep within us, and enriches all our lives. The archetypes that move in those stories move in all of us. I loved reading again Bilbo's final poem...... brought tears to my eyes, as it does every time I hear it. Are your books available in NZ bookshops? Congratulations again David and thanks for sharing your story.