Soft Power and Influence

Keep Your Eyes and Ears Open

Ani O’Brien recently wrote a piece demonstrating the way in which particular approaches and ideologies gain a hold and increase in traction. She commenced the article by describing the phenomenon. She characterized it as WEIRD. I characterize it as the soft power of influence (not to be confused with “influencers”.)

Here is what Ani had to say:

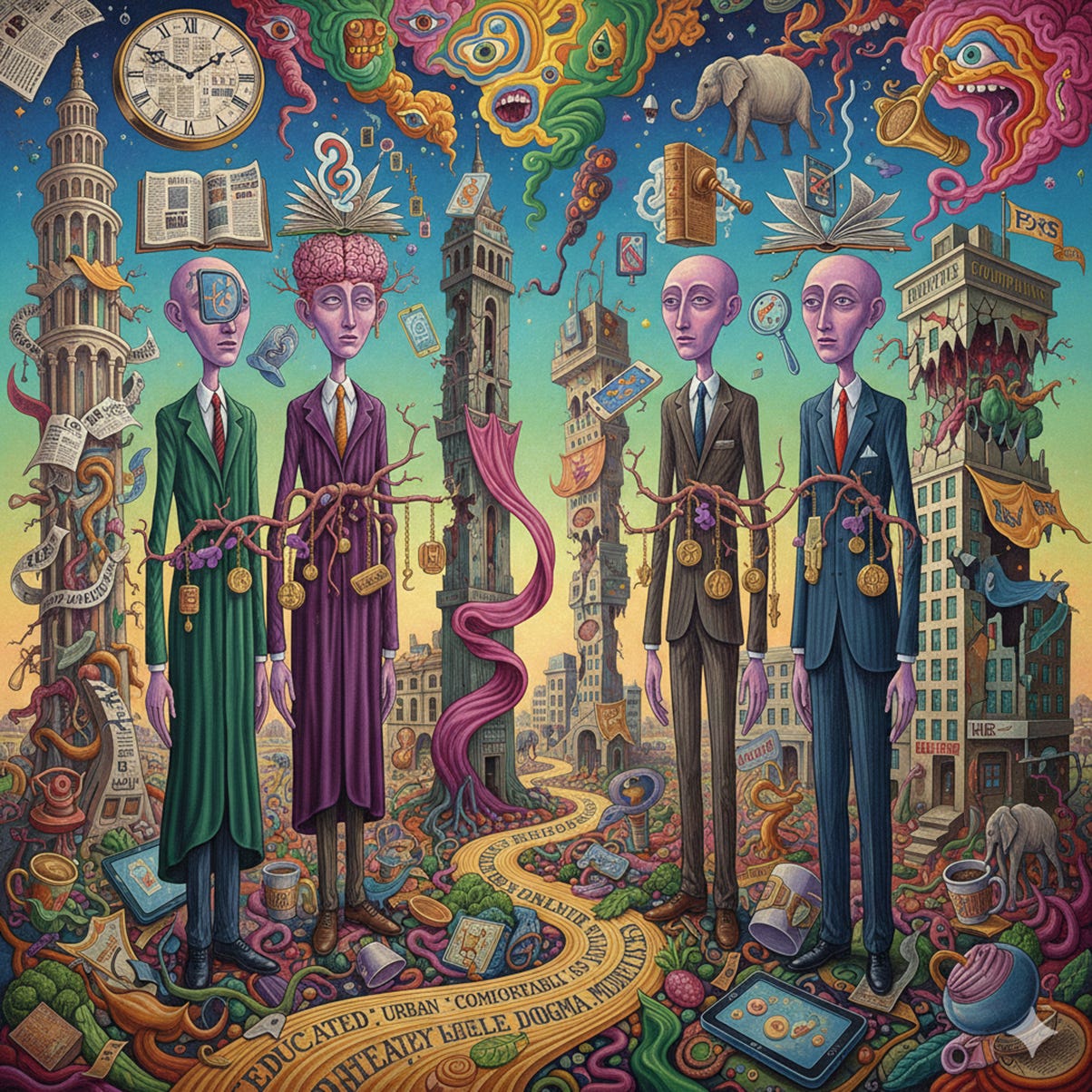

“Another piece about that class of people who seem to sit at the centre of far too many of our institutional and cultural failures. I still struggle to know exactly what to call them. Over the years I’ve tried on labels like the laptop class, the lanyard wearers, the chattering classes, and the woke elite. None of them quite capture the whole phenomenon, but everyone knows roughly who is being described. These are the people who dominate our cultural power centres: media, academia, politics, and the bureaucracy. Sometimes I also include HR departments in ‘big corporates’ as they tend to mimic the social behaviours. They are overwhelmingly educated, urban, comfortably middle class or wealthier, socially liberal to the point of dogma, and deeply wedded to a set of ideological commitments that usually travel under the banner of “wokeness”.

What makes this group so powerful is not just where they sit, but how they reinforce each other. Ideas are generated in academia, often in the form of postmodern or identitarian theories that are incubated in journals through a kind of incestuous peer-validation process (read Cynical Theories!). Those ideas are then picked up by bureaucrats and policy advisers, translated into frameworks, guidelines, and public service orthodoxy. The media reports on these frameworks as settled truth, not as contestable ideology, and treats dissent not merely as incorrect, but as dangerous, immoral, and malignant. NGOs then cite the media and the academic literature to pressure politicians, who are browbeaten into adopting policies they often barely understand, let alone genuinely believe in. Around and around it goes, a closed loop of self-referencing authority that presents itself as consensus.

This class is also remarkably insulated from the material consequences of the world they largely shape. During Covid, they stayed home on their laptops, having Friday drinks via Zoom and daily mental health check ins, while delivery drivers, cleaners, supermarket workers, and tradies absorbed the risk and impacts. Their jobs are stable, credentialised, and protected. They do not live with the same precariousness as the working class. Now, long after we have tried to memory-hole the trauma of Covid, they resist returning to offices with a fervour usually reserved for civil rights struggles. For all their lecturing about privilege, they are its clearest modern expression. And they have used that privilege to drive cancel culture, to socially punish dissenters, to enforce DEI regimes, identity politics, and ever-narrowing boundaries around acceptable thought and speech.

They increasingly behave as if their views are not merely opinions but institutional defaults and disagreeing with them is treated as a threat to public safety. They do not see themselves as one interest group among many, but as educators of a backward population. The rest of society is framed as ignorant, unenlightened, bigoted, you know, “deplorables” who must be coerced, shamed, or forced into compliance. Sneering contempt for “ordinary people” sits just below the surface, occasionally breaking through in moments of frustration or moral panic. Disagreement is not engaged with, it is pathologised and to dissent is not to be wrong, but to be racist, transphobic, anti-science, or morally defective.

One of the more useful labels I’ve seen applied to this group comes from academia itself in a kind of almost self-aware anaylsis. That is “WEIRD” which stands for “Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, and Democratic”. Originally coined to describe the demographic skew in psychological research samples, it turns out to be an eerily good descriptor of the people whose opinions now dominate our institutions. These are societies, and more specifically, sub-cultures within them, that have unusual psychological and moral priors compared to the global majority. Increasingly, even academics are acknowledging that what gets presented as “what people think” is often just what WEIRD respondents think, eg people with the time, resources, confidence, and sense of entitlement to participate in surveys, panels, consultations, and advisory groups.

My view, stated plainly, is that this power becomes dangerous when it turns into hostility toward the population these institutions are meant to serve. Their default posture is suspicion toward the general public, Western culture, and the historical inheritance that underpins liberal societies. Western failures are treated as defining, Western achievements are minimised or dismissed as morally compromised. Narratives that frame the West as uniquely bad, particularly those that centre guilt, identity, and power, are welcomed and amplified, especially when they can be presented as “speaking truth to power”.

This does not function as healthy, corrective self-criticism. By persistently delegitimising our civilisational foundations, these institutions weaken the shared cultural confidence and trust on which liberal democracy depends. The result is institutional self-sabotage and a steady hollowing-out of the norms, assumptions, and loyalties that allow pluralistic societies to govern ourselves at all.

I agree with Ani’s commencing characterisation –

[These] are the people who dominate our cultural power centres: media, academia, politics, and the bureaucracy. Sometimes I also include HR departments in ‘big corporates’ as they tend to mimic the social behaviours. They are overwhelmingly educated, urban, comfortably middle class or wealthier, socially liberal to the point of dogma, and deeply wedded to a set of ideological commitments that usually travel under the banner of “wokeness

Certainly I would emphasise the bureaucracy as a nesting place for these people. The middle and upper management levels are festooned with bureaucrats who seems to think that they have a freehold on – well, everything. And when ever anyone wishes to advance a different perspective it is often – in my experience anyway – politely but firmly dismissed. Once decisions have been made they cannot and will not be reversed. Although there may be “consultation” it is no more than window-dressing designed to give the illusion to the masses that they do have a say but in reality the policies have been decided and the “consultation” box has been ticked. This approach is often enhanced by the way in which consultation questions may be phrased – based on a number of irrevocable assumptions that inevitably can lead to only one conclusion.

Ani sums the problem up in this way

They increasingly behave as if their views are not merely opinions but institutional defaults and disagreeing with them is treated as a threat to public safety. They do not see themselves as one interest group among many, but as educators of a backward population. The rest of society is framed as ignorant, unenlightened, bigoted, you know, “deplorables” who must be coerced, shamed, or forced into compliance. Sneering contempt for “ordinary people” sits just below the surface, occasionally breaking through in moments of frustration or moral panic. Disagreement is not engaged with, it is pathologised and to dissent is not to be wrong, but to be racist, transphobic, anti-science, or morally defective.

In recent times the way in which certain policies of the members of the Coalition Government have been derided provides an illustration. I recently wrote an article in which I stated that I thought that the Regulatory Standards Act was a good piece of legislation. There were a few “Letters to the Ed” on this point one of which posed the question that was I aware of the thousands or submissions opposing the Bill that had been filed with the Select Committee. Critics of my position have included some who would fit perfectly into Ani O’Brien’s characterization. Some argue using the “weight of her authority” as well as a demeaning and patronizing tone. Although some profess to engage with the issue that rarely happens and the position put forward is clearly ideological and diametrically opposed to anything that David Seymour does.

Ani refers to an article by David Chen reporting on a study that suggests that some of the drugs that are classified as harmful and not so and that perhaps the law needs to be revisited based on the apparent absence of harm caused by these drugs. The study in question has been carried out by an academic.

I am not going into the details of Ani’s critique. Her article speaks eloquently for itself. There were just a couple of issues that arise because it may well be that it is not just the soft power of the expert coming into play here but a position that is aided and abetted by the journalist. At no time in the article does there appear to be a contrary view put forward. No discussion of the harms that are cause directly and indirectly by drugs. But that is clear. One has to spend some time in the criminal justice system to understand the harm that drugs do.

The other issue is a societal one and deals with the distribution of drugs. As we all know you can’t buy cocaine over the counter at a pharmacy but there are some dark and shady characters who can make it available. And if they don’t wear them themselves they are backed by members of the various gangs around New Zealand who are well known for their involvement in the drug trade. Drugs, if anything, are the raison d’etre for gangs. And one would think that they would be targeted for this aspect of their operations. But as we all know gangs get a free pass in this country. Oh sure – wearing a patch in public is unlawful but that is a minor aspect of the issue. Rather than confront the gangs our officials prefer to “negotiate” with them and in doing so validate not only their existence but also their activities.

But enough of the drug issue. There is another example of Ani’s soft power influencers at work and this has been amply illustrated in an article by Geoff Parker which was published in the Herald on 6 January. It was entitled “Aotearoa, a name and a choice” and was an answer to a Herald editorial supporting the use of Aotearoa New Zealand as our national identity.

Mr. Parker dissects the argument and expresses his concern as being one of how language is being used as a political instrument rather than a cultural courtesy. And the way that this language is used is by those whom Ani describes in her piece.

Mr. Parker develops the problem in this way:

“In New Zealand, “Aotearoa New Zealand” is increasingly adopted not through public mandate, but through government departments, media organisations, and publicly funded institutions acting unilaterally.

That distinction matters in a democracy.

Language, when embedded in official use, carries authority. It signals not just recognition, but endorsement.

I believe the strong reaction to the use of Aotearoa exists - not because people are confused, but because they recognise a pattern.

For decades, New Zealanders were told that Treaty settlements were “full and final”, that bicultural recognition would sit comfortably alongside a shared civic identity, and that no one would be compelled to adopt new symbols or terminology.

Yet the ground continues to shift. What was once optional becomes expected; what was once ceremonial becomes normative.

It is not unreasonable for people to question where that process leads.

The editorial asserts that English remains dominant, and therefore no loss is occurring. But dominance is not the point. Consent is.

Shared national symbols work best when they arise from broad agreement, not from a sense that change is inevitable and resistance is suspect.

Calling “New Zealand” neutral because it has “carried power unchallenged” reframes history through a contemporary moral lens.

New Zealand is not a placeholder name awaiting correction. It is the name under which a democratic state formed, institutions developed, wars were fought, rights expanded, and millions - all New Zealanders alike - built their lives.

That history is not diminished by acknowledging what came before, but neither should it be casually recast as morally incomplete.”

Mr. Parker’s discussion provides another example of Ani O’Brien’s people who dominate our cultural power centres: media, academia, politics, and the bureaucracy and demonstrates the way that they work.

Perhaps the examples that have been given may assist in this way. Care must be taken in analysing and critiquing public statements – either direct or indirect. And rather than grumble about them, put forward an alternative view.

Qudos to the Herald for publishing the editorial that it did and then giving Mr Parker column inches to rebut. Perhaps this is indicative of the changing editorial policy of that newspaper.

But the soft power of those who dominate the power centres must be met with push back.

Excellent thanks David.

IMO, Mr Parker is 100% right when he states:

"the strong reaction to the use of Aotearoa exists - not because people are confused, but because they recognise a pattern".....

Regarding the flag referendum, I believe the vote was to not change the flag mainly because the push to change it came from the class that Ani described, not a groundswell of desire from NZers. And the irony of the previous referendum of overwhelming public opinion having been completely ignored was not lost on voters.