My doctoral thesis looked at the way in which a new technology (the printing press) influenced law and legal culture between 1475 and 1642 in England.

One of the research questions involved an exploration of the way in which the authorities in Early-modern England attempted to control contrarian content and also the means by which it was produced. How could the State regulate information flows and new information technologies. The printing press was in fact the first information technology and interestingly enough the State is still, even today, trying to do that. The following example is instructive.

In a rush of blood to the head, and with a level of breathtaking arrogance so typical of the Left that believes that the State knows how individuals may best live their lives, the Australian Government (Labour, of course) has introduced a Bill proposing to make internet platforms responsible for controlling misinformation and disinformation (being messaging that does not conform to the State line and that may be harmful to it) as well as a proposal to ban young people under a certain age from accessing social media.

Having studied the way in which States attempt to control new information technologies and the flow of information, some with success although they are in the main highly regulated and authoritarian states, others wilth a modicum of success mainly by the imposition of licensing regimes, I say to the Australian Government, good luck with that.

Part of my doctoral study involved an investigation of the way in which Henry VIII and his State apparatchiks tried to control the messaging surrounding the reformed Church and the Break with Rome in the 1530’s and 1540’s.

The first thing to understand is that Henry replaced the Pope as the head of the Church in England (not the Church OF England – that came later). That meant that Henry had the last word on matters of doctrine and the exercise of religious belief.

Another thing to remember was that Henry never travelled the Martin Luther Reformist path. He remained an adherent to Catholic doctrine. True, his wives Anne Boleyn and Catherine Parr favoured a Reformist approach but Henry, although vacillating on such things as the availability of a Bible in English, was a conservative in terms of doctrine.

The way things developed was that contrarian beliefs that were critical of Henry’s doctrinal approach were seen to be criticisms of the authority of the King. Not only, therefore, was the expression of those contrarian views heresy. It was also treason. The outcome for the dissident would be the same. The only difference would be in the methodology of departure.

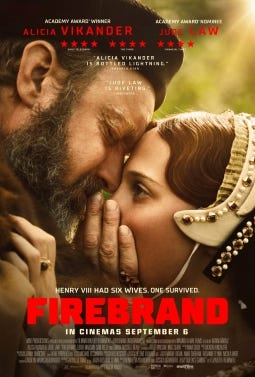

So it was with a level of interest that we went to see the movie “Firebrand” playing at the British and Irish Film Festival. It was very well done with Jude Law in the role of Henry in the last and most tyrannical phase of his reign and Alicia Vikander as Katherine Parr. It takes some historical liberties as these movies tend to do, but certainly Katherine favoured the Reformist side and had authored prayerbooks which was a risky enterprise in those days.

In summary the story is that Katherine was named Regent while Henry led his army in France. Katherine looks after Henry’s children, Mary, Elizabeth and Edward. Katherine takes risks to meet up with an old friend, Anne Askew, who is preaching Protestantism (of which more later).

When the king returns, increasingly ill and paranoid, Katherine finds herself fighting for her own survival as Henry's courtiers increasingly try to turn the king against her. Katherine gets pregnant, but has a miscarriage.

Bishop Gardiner believes Katherine’s views are dangerous, and convinces Henry to have her arrested. She is locked in a dungeon, but Henry soon frees her, and she goes to his bedside and kills him in 1547.

There is no evidence that Katherine murdered Henry, nor that she was imprisoned. Gardiner did obtain an arrest warrant but Henry revoked it.

Katherine subsequently married Thomas Seymour but she died in 1548 at the age of 36. Her funeral, held on 7 September 1548 was the first Protestant funeral in England, Scotland or Ireland to be held in English.

Katherine’s religious views were viewed with suspicion by anti-Protestant officials such as Bishop Gardiner. Although brought up as a Catholic, she later became sympathetic to and interested in the "New Faith". By the mid-1540s, she came under suspicion that she was actually a Protestant. This view is supported by the strong reformed ideas that she revealed after Henry's death, when her third book, Lamentation of a Sinner, was published in late 1547.

A focal point of the movie is the support that was given by Katherine to Anne Askew who was turned out of her husband’s house because of her Protestant beliefs. She unsuccessfully sought a divorce and sought support from friends at Court including Katherine Parr. It must be remembered that much of England still adhered to Catholic ideology, and reformers -- especially female reformers such as Askew -- were often perceived as serious threats to the religious status quo. Parr was initially able to obtain a pardon for her friend but Askew continued to publicly express and preach her doctrinal dissent.

The prevailing religious culture of Anne's time, summed up by bishop Stephen Gardiner, viewed "plain speaking" with suspicion, a tactic used by the devil to spread heresy: "and where planes may deceive, he make then his pretence to speak plainly and professes simplicities.”

In the last year of Henry VIII's reign, Askew was caught up in a court struggle between religious traditionalists and reformers. Stephen Gardiner was telling the king that diplomacy – the prospect of an alliance with the Roman Catholic Emperor Charles V – required a halt to religious reform.

The traditionalist party pursued tactics tried out three years previously with the arrests of minor evangelicals in the hope that they would implicate those who were more highly placed.

The people rounded up were in many cases strongly linked to Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, who spent most of the period absent from court in Kent: Askew's brother Edward was one of his servants and Nicholas Shaxton (who was brought in to put pressure on Askew to recant) was acting as a curate for Cranmer at Hadleigh. Others in Cranmer's circle who were arrested were Rowland Taylor and Richard Turner.

The traditionalist party included Thomas Wriothesley and Richard Rich, Edmund Bonner and Thomas Howard.

In 1546 after two previous arrests, Anne Askew was arrested and was tortured in the Tower of London. The torturers, Lord Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley and Sir Richard Rich, used the rack, but Askew refused to renounce her beliefs. The intention of her interrogators may have been to implicate Queen Katherine Parr through her ladies-in-waiting and close friends, who were suspected of having harboured Protestant beliefs.

On 18 June 1546, Askew was convicted of heresy, and was condemned to be burned at the stake. Due to the torture she had endured, she had to be carried to the stake on a chair. She was burned to death along with three others.

They were dangerous times in which to express a dissenting or contrarian view.

These thoughts occupied my mind after the movie and I reflected upon an event that I attended the day before – an event put on by the Free Speech Union at which an Anglican priest and Oxford academic – Nigel Biggar spoke. Others spoke as well, as one might expect. Contrarian views were the order of the day.

And although the rack and the stake are no longer employed there are more subtle and insidious ways in which the freedom of expression may be fettered.

There were four panel discussions at the event. David Seymour (a coincidence of names given the role of the Seymours in later Henrician politics) was involved in one. I was involved with David Parker in a discussion about free speech and the law. There were discussions about the media and speech, academic free speech and political action and free speech.

A member of a media organization had been invited to participate in one of the panels. For some reason this person mentioned or sought permission from an employer and was advised that attendance and participation would be unwise. That person did not attend. Pressure had been brought to bear which inhibited not only that person’s freedom of expression but also the freedom of association. Unlike Henry VIII’s time doctrinal purity was not advanced as a reason. It is difficult in these time to imagine any employer doing that but it would not surprise me if they did.

It was an encouraging afternoon – more encouraging than I thought it would be. Professor Biggar – who has written a book entitled “Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning” was a brilliant and inspiring speaker as only a senior Oxford academic could be. I shall write about his book in a later post – I am presently reading it but in essence Professor Biggar has called for a moral reappraisal of colonialism. Contemporary historians, he believes, have made us feel too guilty about Britain’s colonial past. We need to recognise not just the bad but also the good of empire. Colonialism is his attempt to create such a moral balance sheet.

Biggar’s views are not popular. He himself has been the subject of “cancelling” attempts because of his point of view. Not unsurprisingly his book was unfavourably reviewed in the Guardian.

One of his messages at the event – and there were many and I did not have my notebook with me to jot them down (mea maxima culpa) – was that the approach of the Left with their ideological anchors and cancellation of ideas, a distinct unwillingness to engage in discussion, and an outrage that anyone would disagree with them on anything, are essentially challenging the intellectual underpinnings and gifts of the Enlightenment that was spread by colonial activity. There were some terrible things done by colonization but in the main the liberal democracies around the world have arisen primarily from British colonial activity. To try and undermine that heritage is to strike at the heart of Western Enlightenment ideals.

But no solution is offered. No alternative is proposed. And in these troubled times it takes a certain amount of courage to speak up and to advance a position that differs from that of the “orthodoxy”. We have seen this particularly over the COVID years when the expression of contrarian views was, and still is, being suppressed.

Those who advocate an alternative position are demeaned. Reality Check Radio is referred to by the term Rabbit Hole Radio (although when Alice followed the rabbit down the rabbit hole it was out of curiosity) and the Platform is seen as a right wing mouthpiece which well it might be, but those on the Platform and RCR should be an are entitled to have their say.

The consequences for contrarianism may not be as dire as the rack, the pyre or hanging drawing and quartering but they are present nonetheless. The Left uses the tools or cancellation – prohibiting speech, preventing the exercise of the freedom of expression by shouting down or threatening disruption, avoiding argument and debate by the use of veto words liker racist or sexist, misinformation or disinformation and they bring pressure to bear by way of threats of embargos.

It takes courage in the face of this opposition to put one’s head above the parapet and voice an opinion, to advocate for a position.

The FSU comes in for criticism mainly from people who have a relativistic view to free speech. Free speech to many is speech with which they agree. But the FSU is entirely content neutral. It is the expression of a point of view and the right to hear that expression that is critical.

The FSU doesn’t necessarily endorse a point of view, but rather the right to express it. So even advocating for the right to express a view, regardless of the view, is seen by some as “unsafe” or “wrong”.

But if points of view go unexpressed those who do express their point of view control the narrative and fill the room with a minority of voices. Admittedly by means of a secret ballot (which has its origins in a time when it was recognized that the outward expression of a political view could have adverse consequences) a majority of the United States voters have expressed their dissatisfaction with the status quo. To those who were really listening – and clearly Donald Trump was one of them – the result was not a surprise. But it was to those who did not hear the murmuring.

But there should be more than mere murmuring. There should be discussion – a clear expression of views. Only then will it be clear whether or not the loudest voice in the room is a minority or reflective of the majority view.

The obligation must be – as Denethor said to Pippin in “The Lord of the Rings” – to speak and be not silent.

Lots of parallels between the printing press and the internet. Have you read the Shardlake books? I assume you have but if not you would like them.

Thanks David. I had an unmissable date when Biggar spoke here, sadly. Pleased to read this & hear him on other platforms. I joined the FSU when it was a coalition, Southern & Molyneux days.

Speaking of platforms & rabbit holes, Leah Panapa on The Platform told me I had gone down one when I criticised her & another's blind adherence to the new wave gender orthodoxy when they spoke of the male boxers posing as females at the Olympics as 'she'. The irony.

Enjoyed the Wolf Hall tv series.

I cannot fathom what planet Albo et al are on. Well, I can.