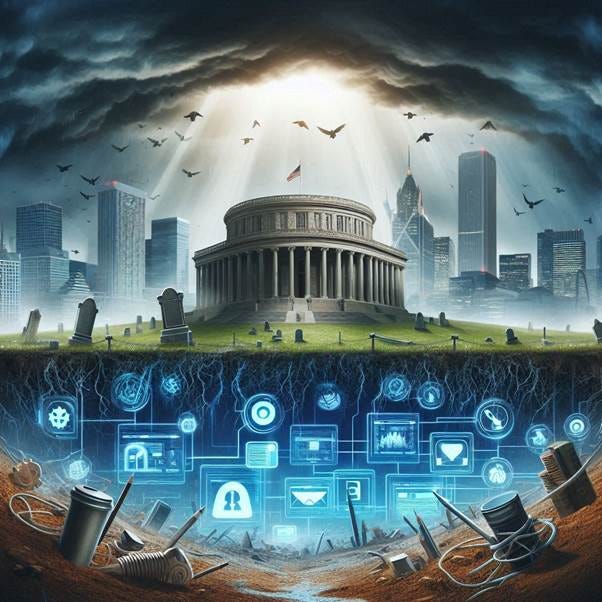

Suspended Animation

The Safer Online Services Proposals are not Dead But Merely Sleeping

This is an article about an article that calls for the resuscitation of the Safer Online Service and Media Platforms (SOSMA) proposals of the Dept of Internal Affairs, which was driven by the Ardern/Hipkins Government.

The arguments advanced in the article are not new. They are based on what is perceived as “unsafe” or “harmful” online content from which users are not protected.

I have written on the objectionable and legally questionable proposals in SOSMA in a three-part commentary on the SOSMA proposals.

Part 1 (July 2023) is here

Part 2 (August 2023) is here

Part 3 (August 2023) is here

The matter needed further discussion and some answers to questions and answers (August 2023) can be found here

My final commentary on the SOSMA proposals (August 2023) can be found here

In May 2024 I discussed and critiqued the SOSMA proposals.

Finally the article here tells of the demise of the SOSMA proposals.

The difference in this article is that the authors have grounded their arguments on aspects of human rights law but their assertions are general only and there is an absence of referencing or authority.

The familiar tropes and arguments advanced by those who would seek regulation (read “censorship”) of online platforms underpin the arguments advanced.

What may be a solution that is less invasive is to amend the Harmful Digital Communications Act 2015.(HDCA)

This Act already provides relief for individuals and would meet many of the concerns expressed by the authors, but which they have chose to overlook either because it is inconvenient to their argument or from ignorance of the solutions available.

The amendment I would suggest is to make the remedies in the HDCA available to members of groups rather than restricting the availability of those remedies to individuals.

But what the article does establish is that the appetite for online regulation or censorship of content is still present and the desire to breathe fresh life into the corpse of the SOSMA proposals is still present and would seem to be flourishing.

This article probably stands as a warning sign. Should a left-wing Government assume power it is highly likely that the zombiefied corpse of SOSMA will burst forth from its grave. SOSMA is not dead. It is but sleeping.

I have reproduced the article that appeared in Newsroom in full and have inserted my commentary in italics where relevant. I prefer this approach because it enables me to address the issues as they arise rather than place my own interpretation of the article and follow it with analysis. In addition, readers can assess the strength or weaknesses of my comments alongside the text of the article.

NZ has no clear direction on online safety regulation

Rather than placing the burden on victims, the Government should place the burden of online safety on social media platforms

Analysis: We are not currently regulating online media in this country, despite this resulting in serious problems for us, as was brought so readily into focus by the 2019 Christchurch terrorist attack and extremist reaction to our national pandemic response.

Most people are not interested in discussing the finer points of regulation. You generally only become aware of regulation when it doesn’t work, or worse, when we don’t have any. And that’s particularly the case for our online world.

This is not correct. Present legislation includes the Harmful Digital Communications Act 2015 and the Films, Videos and Publications Classification Act 1994. This latter legislation was deployed shortly after the 2019 Christchurch terrorist attack and the live stream by the terrorist was declared objectionable making it an offence to possess or distribute it.

Aotearoa New Zealand’s media regulation landscape is one that has developed organically over time. As each new media form emerged, we created a new regulatory entity for it, each distinct, disconnected, and quite different. The result has been a high degree of incoherency.

There are a number of imperatives when it comes to media regulation and that regulation has developed on an ad hoc basis.

The imperatives involve the importance of freedom of expression – the right to impart and receive information – and associated issues such as freedom of the press.

At the moment there is no State-based regulatory structure in place for the traditional press. There was a move in 1972 by the Government to impose a form of regulation and the industry took steps to forestall those moves by forming the Press Council (now the New Zealand Media Council)

Following a report by the Law Commission about means of regulating news media and new media an Online Media Standards Authority was formed – rather like the Press Council but for online content. Like the Press Council it was voluntary and ultimately merged with the Press Council which was renamed as the NZ Media Council.

Broadcasting is regulated by the Broadcasting Act 1989 and the Broadcasting Standards Authority.

The interest of the State in broadcasting goes back to the 1920’s when radio had been introduced. State control of broadcasting and the elimination of any competitive element in the field was a feature of this form of information dissemination. But because the State controlled broadcasting it also had an interest in the quality of the content that was broadcast.

As the need for competition became apparent and broadcasting businesses began to push the boundaries attitudes began to change. But the State was not prepared to relinquish the control that it had enjoyed. Little by little things began to change until 1989 and the new Act which established the Broadcasting Standards Authority. This organisation was concerned with content rather than other more technical aspects of broadcasting, and established a system of Codes which set standards expected of broadcasters. This has been the model that continues to today. Thus the State interest in broadcasting content continued although at an arms length.

The Internet is a communications technology and enables a number of different means of communication using the backbone. Thus organisations which would normally have used broadcasting spectrum and which would have fulfilled the definition of broadcasters have been able to communicate their message using Internet based protocols. This raises a challenge to broadcasters who fall within the scope of the 1989 Act. A further issue is that on-demand and on-line providers of content are specifically excluded from the scope of the Act.

But importantly, unlike broadcasting, the State has not had an interest in managing and controlling Internet technologies. Indeed, in the Broadcasting Act it has specifically excluded on-line and on demand material from the scope of the Act. Thus to regulate the new technology means developing a regulatory framework rather than, as was the case with broadcasting, incrementally loosening the chains of State control.

These anomalies are currently being considered by the Ministry of Culture and Heritage who have called for submissions on Media Reform proposals. The Regulatory landscape is the lynch-pin for these proposals.

The authors have conveniently overlooked the presence of the Code of Practice for Online Safety and Harms which is a form of self-regulation by the platforms. Details of the Code may be found here.

This is an untenable situation in a 21st century context where we have had no real regulation of online content and where the walls between different media forms have been broken down.

The authors fail to identify why the current situation is untenable and fail to consider the Media Reform proposals as a means of online content regulation. By virtue of the statement that the walls between different media forms have been broken down, they fail to recognise the paradigmatic change that has been wrought by digital technologies.

We are living in a rapidly developing Digital Paradigm where continuing disruptive change and permissionless innovation are realities. These qualities alone mean that any form of regulation is either going to be obsolete or very wide-ranging to anticipate changes in communications technology. This is known as “future-proofing” and is an element of regulation that Wellington bureaucrats are not good at.

In 2024, New Zealand was tantalisingly close to solving the online regulation problem – but the project was abruptly dropped.

What happened?

This is the sharp end of the article. It identifies in very broad terms a problem that involves the regulation of Internet based content – what we say or read – and heralds a polemic that at once will be critical of the abandonment of a perceived solution (although that solution was so wide ranging as to amount to a form of State control or surveillance on on-line content) and suggests a re-institution of a programme that the Government rightly brought to a halt.

Safer Online Services and Media Platforms Review

A review of Aotearoa New Zealand’s media regulation landscape began in 2021, hot on the heels of the Royal Commission of inquiry into the terrorist attack on two Christchurch mosques.

Government priorities at the time included strengthening social cohesion and addressing the emerging problem of mis- and disinformation and extremist content on social media.

The then Minister of Internal Affairs, Jan Tinetti, hoped to create a new simplified media regulatory framework that would minimise harm arising from all media, but especially from social media.

In 2023, Te Tari Taiwhenua/Internal Affairs released a discussion document outlining what a proposed new framework would look like.

Drawing inspiration from overseas models, Internal Affairs proposed a new, independent regulatory body to promote online safety. Legislation would set industry minimum standards and codes of practice, developed with industry (for example, large social media companies), and would provide specific and legally enforceable online safety obligations.

This is a correct summary of what took place but regrettably skips over the details of the proposal – and it was only a proposal – that made it objectionable.

Public consultation revealed broad support for the regulation of social media platforms, especially among relevant organisations and community groups.

Define relevant organisations and community groups. Many of the submissions were concerned at the effect of robust and critical discussion of a point of view or a position taken by various groups. The usual mantra is that such discussion raises concerns about “safety” which seems to suggest that the only content that is safe is anodyne in nature and contains not a skerrick of criticism of a group or point of view.

This is where the concept of social cohesion comes in. By limiting the way in which people express themselves, especially about others in the community, that community has a greater element of cohesion or sameness about it. To step outside the boundaries of that sameness is a threat to the community because the sameness is challenged.

Thus it can be seen from this rather simplistic example how the social cohesion basis for content regulation online is a direct threat to the freedom of expression which is not only to impart information (the freedom of speech element) but to receive information (the freedom to obtain information)

However, the proposal received pushback from individual submitters, citing concerns about freedom of expression. The vast majority of these submissions were made using Free Speech Union and Voices for Freedom templates.

Having failed to define the “relevant organisations and community groups” the authors hasten to name and inferentially demonise those who were opposed to the suggestions contained in the SOSMP proposals. The fact that templates may have been used is irrelevant. What is relevant is that individual citizens were prepared to stand up and oppose the proposals. The individuality of those citizens is inferentially criticised and belittled because they used a common form document.

Relying on these opposing voices, Internal Affairs Minister Brooke van Velden, under the newly elected National-led coalition Government, scrapped the proposal in 2024.

How do we know that reliance was placed solely upon the opposing voices or that there were other elements of principle that the Minister relied upon? This is a sweeping statement that lacks an evidential authority or referencing and is another inferential swipe at the Free Speech Union and Voices for Freedom.

No replacement plan or policy has been announced since to address online harm, leaving New Zealand without any clear direction on the matter.

Correct that no “replacement plan or policy”(sic) [It should read no replacement plan nor policy] has been announced because it is not seen as a priority.

However there has been a debate raging about the fate of mainstream media and how the BSA can be adapted to deal with new media offerings.

Perhaps the biggest irony about this is that the media landscape was examined thoroughly by the Law Commission in 2013 but there seems to be collective amnesia about that detailed report and certainly no policy based consideration of its proposals apart from a side report (a Ministerial Briefing paper) which led to the Harmful Digital Communications Act 2015 – a piece of legislation conveniently overlooked by the authors of the paper.

The assertion also overlooks the fact that online harassment is on the way to becoming a crime as a result of recent legislation introduced to Parliament.

But online harm has only intensified in recent years, particularly misogyny and violent extremism.

Some harmful online behaviours are also human rights violations

Taking online misogyny as an example, the targeting of women with harassment, including threats of sexual violence and death, image-based sexual abuse, including deepfake porn, and doxxing (the disclosure of private information without consent) are all forms of online gender-based violence.

Such violence can cause victims to fear for their physical safety and may engender a sense of powerlessness. This can lead women to self-sensor (sic – I think censor is the word intended) their comments online or leave social media platforms altogether.

The examples given of what is classified by the authors of misogynistic communications are concerning but there is something of a leap in the discussion. Are “threats of sexual violence and death, image-based sexual abuse, including deepfake porn, and doxxing (the disclosure of private information without consent)” by virtue of that fact alone examples of misogyny or on-line gender-based violence. If a man is a target of doxxing is this a form of gender based violence (it certainly is not misogyny).

This is an example of the use of stereotypical language in a debate that generalises issues and transforms them into a societal problem.

Therefore, online gender-based violence breaches women’s rights to freedom of expression, the right to be free from discrimination and violence, and the right to privacy.

I am prepared to accept that there are freedom of expression issues if a person (male or female) feels it necessary to leave a platform or self-censor. There is no compulsion to belong to or sign up to a platform. And because freedom of expression is a two-way street it is not an infringement of the freedom of expression if a user decides to disengage from a platform because the information conveyed on that platform is unacceptable or not a form of expression that the user wants to receive.

It is a common argument that there is a freedom of expression issue here because there is not.

As to self-censoring that happens all the time. It is rare if people drop all the filters and say exactly what is on their minds. The English language is extremely versatile in this regard and provides numerous resources with which people may express themselves that range from the anodyne to outrageous. For myself I prefer reasoned discourse without resorting to Anglo-Saxon expletives. Although the use of such terms demonstrates at times a poverty of language they replace or subvert the development of an argument based on reason.

The human rights implications require the New Zealand government to fulfil its legal obligations under international treaties to prevent such online harm.

Doing nothing to protect vulnerable groups from online harm is not an option. In fact, doing nothing risks the government being in breach of international human rights law.

Chapter and verse for the international instruments would be helpful. A sweeping assertion that we are in breach of human rights law typifies much of the debate in this area and prevents informed debate.

Lest it be suggested that I should turn up the relevant treaties and wade through them to find what may (or may not) be the authority relied upon, I have neither the time nor the inclination to spend my declining years doing research that others should have done and should have referenced. The authors are academics. They know they way these things are done.

In a report for Hate & Extremism Insights Aotearoa in 2024, Jenni Long warned that the relationship between online misogyny, hate speech and disinformation signified regression in structural gender equality and democratic stability.

This sounds like a mixture of bureaucratic and academic argot to me. How is democratic stability under threat or is this another term for social cohesion?

We argue that urgent action is required.

Where should Aotearoa go from here?

It’s time to dust off that proposal.

The final ‘Safer Online Services and Media Platforms’ report that came out from Internal Affairs at the end of 2023 was the product of years of very good and necessary work by the department.

These efforts should not be vain, especially given the obvious need to regulate online arms, but this is not to say the proposal is perfect.

For instance, the primary operating process of the new regulatory body was to work with those within the media industry to develop codes of practice that would form the regulatory standards that the different forms of media would need to adhere to.

Probably there is little to debate in these paragraphs other than to say that SOSMP was not the product of hard work but rather lurched along until what was provided at last, after many delays [that were typical of the Ardern/Hipkins way of doing things] it became available.

An independent regulator that works with community groups first

While these standards would be formed with good practice internationally, to ensure alignment for what are effectively trans-national global media companies, their development would largely be industry directed. The process then would be to liaise and consult with community groups to make sure the standards were fit for purpose, but the primary relationship for the media regulator would be with industry.

We argue that this is the incorrect prioritisation. If the intent behind the regulatory standards is to prevent harm to our communities, harm that is already occurring, and compoundingly so, then communities and the groups representing their interests and concerns should be the starting point, not a consultative focus later.

Taking a human rights approach, the voices of the marginalised should be prioritised when developing any codes of practice.

This is not to say industry requirements are irrelevant, but rather that they should be designed to support the needs of communities first. We would also argue that co-governance arrangements should also be baked into the regulator. It is absolutely crucial that guaranteed and allocated representation for Māori is provided for to ensure that a proper partnership is embodied.

The authors clearly have little confidence in self-regulation which has been the benchmark for news media since 1972. At the same time they have overlooked or ignored the New Zealand Code of Practice for Online Safety and Harms which provides an example of self-regulation in actions.

Safety by design

According to international human rights law, to prevent human rights abuses the Government needs to invest in proactive measures. Rather than placing the burden on victims, the Government should place the burden of online safety on social media platforms. Therefore, codes of practice should require platforms to minimise harm at every point – from design to implementation.

No rationale is offered for placing the burden on platforms. The suggestion is that platforms should anticipate the likelihood of “harm” rather than react to a specific allegation of it – which, of course, would have to be proven.

Alignment with overseas standards

Finally, because of the more complex nature of the modern media landscape, the presence of research and policy teams that liaise with the regulators in other countries needs to be prioritised within the structure of the regulator. This is to ensure that not only do we fit with international good practice, but that we align internationally to ensure consistent and coherent requirements on online platforms across borders. Given that the modern media landscape is not bound by location, the strength of our regulation should not be either.

To prevent online harm such as gender-based violence, proactive and legally enforceable measures are essential. The Government must urgently review the necessity for legal regulation to meet its international obligations, protect the human rights of users and fill the regulation gap.

There has been so much good work done, now is not the time to drop the ball.

These are interesting proposals and go some considerable distance beyond what was proposed in the SOSMP discussion document. The focus is on a human rights perspective and the elusive concept of safety.

As I have suggested this term is used to describe content or material that users may not wish to read or hear. To restrict such content is of course censorship.

The simple answer is this. If a user sees, reads or hears content that they do not want to see, read or hear they can become the censor, rather than the State. The answer is to delete the email, close YouTube or Facebook or the comments section on LinkedIn – in other words – use the ultimate censorship device – the off switch

SARAH BICKERTON

Dr Sarah Hendrica Bickerton is a lecturer in public policy and technology with the Public Policy Institute in the School of Social Sciences at the University of Auckland

CASSANDRA MUDGWAY

Dr Cassandra Mudgway is a senior lecturer above the bar at the University of Canterbury's Faculty of Law More by Cassandra Mudgway

Newsroom 6 March 2023