This is the third part of my arc on understanding the importance of the media (singular “medium) of communication. I contend that Mainstream Media which seems set on carrying on its same old business model does not understand this and that is one of the reasons why Mainstream Media is in trouble.

In part 1 I looked at the properties or qualities that underpinned print as a medium of communication. In part 2 I looked at the Digital Paradigm and identified a number of properties which I ordered into a taxonomy.

In this final part I bring the two together and suggest an analytical model which may be deployed and conclude with a look into the future.

Media Models and Regulation in the Digital Paradigm

Once we understand the properties of the Digital Paradigm it becomes clear that although content (and that includes programming) plays an important part from the point of view of audience interface there are underlying technological factors that impact upon the “how” of that interface. That has an impact upon Mainstream Media (MSM) business models as much as it does upon the ways in which regulatory structures may be deployed.

It is important to remember that new information technology paradigms subtly influence our perceptions of information, our intellectual approach to information and our use of information. The properties apparent in one paradigm may not be present in another.

A problem arises where we have become inured to the properties of one paradigm and consider that they apply mutatis mutandis to another without recognising that paradigmatic change introduces concepts that are so utterly different from a former paradigm that our responses, reactions to and assumptions about information are invalid.

This is particularly so when it comes to consider regulatory structures and policies which may be applicable to developments that occurred under one paradigm and that may not comfortably translate to a new one

It is suggested that it is necessary to examine the properties of different information technologies to ascertain whether or not continuing assumptions about the nature of information and its communication are still valid, or whether they must be revisited in the light of the new technology which may have significantly different properties from the old.

When we examine the properties of information communication technologies such as the printing press alongside new digital technologies including computer-based and internet accessible information, it becomes necessary to re-evaluate our responses to and our assumptions of information that is available within the digital paradigm. I have outlined these properties earlier in this discussion.

Some of the ways in which the properties of the new paradigm challenge old models are in the way in which the almost infinite storage capacity of digital systems means that “all the news that fits,” to paraphrase the New York Times masthead, becomes all the news – period. No longer is it necessary for editors to weigh up one meritorious story against another for a limited number of column inches.

Medium specificity has gone as a result of the challenge of technological convergence. This means that news and information dissemination becomes an exercise in multimedia. The defining line between say television with its audio\visual influence and print which is a somewhat more deliberative medium for the consumer becomes blurred as text, audio and video may all form part of the one posting.

The constant availability of information on online systems from a multitude of sources means that the journalistic shoe leather of bygone years has been replaced with “walking” fingers and search engines. The MSM digital journalist’s first port of call for background information on a person is Facebook, Instagram or Twitter and “vox pops” are replaced by a stream of tweets. This constant flood of information and the quality of information immediacy means that the so-called “news cycle” based on edition or broadcast timing has become a constant flow. The competition is not only for the story but for the best telling of it.

Digital technologies enable new channels and tributaries for news content. No longer is the “breaking story” the sole domain of MSM. An example may be seen in the case of Keith Ng who in 2012 published a story about a computer vulnerability in kiosks at the offices of the Ministry of Social Development on the Public Address blog[1]. At the same time as a result of donations that were made on a Givealittle site he became the highest paid journalist in New Zealand.[2] By the time the story was picked up by MSM the real story was about how a blogger had scooped the mainstream.

Online streaming media and on demand content means that “appointment viewing” or “listening” has become a thing of the past. As Lord Neuberger said of the on-demand facility offered by the UK Supreme Court – “justice may be seen to be done at a time that suits you.” So it is with virtually all digital as information persistence asserts itself.

These characteristics emphasise the need for care to ensure that our policies are not based on assumptions deriving from the “old technology”. A different set of assumptions based upon information derived from the digital paradigm must be developed that recognise and reflect its properties. A tension necessarily arises between our print paradigm expectations and those that are apparent within the digital paradigm. Yet there remains a path where the core values that have developed within the print paradigm may still be reconciled with information derived from the digital paradigm.

Applying McLuhan

As I have observed Marshall McLuhan made (among many) two observations pertinent to this discussion. When he said “the medium is the message” – a somewhat obscure remark – he was emphasising that when we deal with communications technologies the content that is delivered is secondary - the way in which the message is delivered is more important. He emphasised this rather crudely when he said that the "content" of a medium was a juicy piece of meat carried by the burglar to distract the watchdog of the mind.

This means that we tend to focus on the obvious, which is the content, but in the process, we largely miss the structural changes in our affairs that are introduced subtly, or over long periods of time.

As society's values, norms and ways of doing things change because of the technology, it is then we realize the social implications of the medium. These range from cultural or religious issues and historical precedents, through interplay with existing conditions, to the secondary or tertiary effects in a cascade of interactions of which we may be unaware.

This is reflected in the second comment that McLuhan made - We shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us. In this case the tools are new communications technologies and they have been and still are changing our behaviours and our expectations of what technology can do – especially in the communication of information. In many respects the tools have shaped what has become the new, converged media landscape.

McLuhan’s Model for Analysis

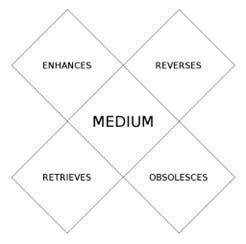

In the late 1970s Marshall McLuhan created a principle called the “tetrad of media effects”.

The tetrad first appeared in print in articles by McLuhan in the journals Technology and Culture (1975) and et cetera (1977). It first appeared in book form in his posthumously-published works Laws of Media (1988) and The Global Village (1989).

The tetrad is a four part construct to examine the effects on society of any technology/medium (that is, a means of explaining the social processes underlying the adoption of a technology/medium) by dividing its effects into four categories and displaying them simultaneously. It helps to explain the aphorism “the medium is the message”.

Visually, a tetrad can be depicted as four diamonds forming an X, with the name of a medium in the center, where the left/right direction reflects the figure/ground association. The two diamonds on the left of a tetrad are the Enhancement and Retrieval qualities of the medium, both Figure qualities.

In essence the Tetrad poses four questions:

What does the medium enhance?

What does the medium make obsolete?

What does the medium retrieve that had been obsolesced earlier?

What does the medium reverse or flip into when pushed to extremes?

A very simple example is with the mobile phone – a communications technology.

The mobile enhanced communication by making it possible wherever we are – place doesn’t matter.

It made landlines obsolete.

It brought back direct communication that was under threat from mass media like TV, but as it developed,

It reversed its original purposes (oral communication) by pushing people to text and digital communication.

Let us now look at the Digital Paradigm generally.

Digital enhances information availability (timing and access) via screens.

Digital therefore makes information transmitted via hard copy print or appointment viewing obsolete

Digital retrieves an enhanced value for wider knowledge and information that has been lacking in the education system.

Digital reverses expectations based on a dependency or reliance upon devices.

Once we understand these qualities we can see that the actual content doesn’t matter but it is the medium must be understood to develop content deliver systems – hence the medium is the message.

Information Expectations

What the technology has done is that it has dramatically changed many of our previously conceived ideas and understandings of information. Our responses illustrate this. The Minister of Justice’s remarks when he made his reference to the Law Commission provide an example. Putting to one side the emotive references to “the Wild West” which are anachronistic and inaccurate (although the term is still being deployed) the subtext of the Minister’s comments amount to the following:

a) People are doing things with information and information systems that they were unable to do before (or could do, but with difficulty)

b) Some of these actions challenge the rules and the framework of rules that have been set up to regulate information delivery systems

c) There must be some way by which the actions which challenge the rules are brought within the existing rule structure or framework

Another way of interpreting proposition (c) is to ask how we can put the future within the constraints of the past. In many respects we find that the behaviour of individuals can be addressed within existing rules.

Regulating Media in the Digital Space.

This position becomes more complex when the focus shifts to what may be termed “institutions” such as the news media. The history of press, radio and television are continuing stories of State involvement with the media to one extent or another, be it at the level of content licensing following the statute of 1662 (print), state ownership and control of radio broadcasting as was the situation up until the early 1970’s or television channel licensing as is the case today. In addition there are the regulatory structures of the Press Council, the Advertising Standards Authority, the Broadcasting Standards authority and the regime under the Films, Videos, Publications Classification Act 1990.

An interesting foray into the monitoring of online content came shortly before the Law Commission released its report “The News Media Meets ‘New ‘Media: Rights, Responsibilities and Regulation in the Digital Age.”[3] That report recommended the formation of a single regulator, conflating the roles of the Press Council, the Broadcasting Standards Authority and the Advertising Standards Authority. By and large membership would be compulsory for MSM organisations but would be voluntary for bloggers or citizen journalists thus entitling them to some of the privileges of journalists.

However, in anticipation of the report in February of 2013 the Online Media Standards Authority (OMSA) was created following talks between TVNZ, Sky/Prime, MediaWorks TV, Maori Television, Radio New Zealand, The Radio Network and MediaWorks Radio. OMSA was industry funded and a self-regulatory body designed to oversee online news and current affairs content standards. Some bloggers such as David Farrar of Kiwiblog and Cameron Slater of Whaleoil joined although Slater later parted company with OMSA.

Almost four years after it was established OMSA members announced that all online publications over which they had editorial control would be under the jurisdiction of The New Zealand Press Council. It has been suggested that there was insufficient work to justify the existence of a separate online regulator. That merged body is now known as the New Zealand Media Council and largely operates in the same way as the Press Council but of course with a wider remit.

Media Convergence

A converged media calls for a revised approach to regulatory structures. Separate organisations can hardly be justified, based on the medium of distribution of content. A single regulator would recognise the fundamental change in the way news is produced, disseminated and accessed in the paradigm of technological convergence. The question is whether this should be by way of industry regulation as is the case with OMSA and the Press Council or a body established by the State.

What must be remembered is that as these the new technologies involving radio and television came on stream the State was very swift to attempt to assert some sort of control over their operation and output. In New Zealand it would be cynical to suggest that there is a political motive for this, although the curious situation where the Labour Party, which then favoured state control, supported the passage of the News Media Ownership Bill which would have released the stranglehold of newspaper ownership then present in New Zealand and which Labour perceived was right-wing, gives some support to the suggestion that within the political sub-conscious there is a media control agenda.

Of course, various levels and intensity of control are possible with monolithic, centralised and capital hungry organisations. In the pre-digital paradigm the costs of setting up a newspaper, radio or TV channel were and still are very high, even without regulatory approval.

The digital paradigm challenges that model. As has been observed, it enables everyone to become a publisher. It is not unexpected that news media should rise to the challenge and we find ourselves in a situation where there is a convergence between broadcast and print media in print media websites, and the use by broadcast media of the various communications protocols enabled by the Internet to provide live streaming of content and content on-demand.

But we must remember that the regulatory structures that have been put in place were all pre-digital and with the monolithic model in mind. And furthermore we must remember that the digital revolution (so called) is in fact evolutionary in effect.

But one of the recurring themes about the current issues surrounding the media is that if financial assistance and the assumption is that financial assistance will come from the Government or by means of a means facilitated by Government action or agency.

This was highlighted by the advice that was given to the Minister of Communications in November 2023. That advice warned the government it may face requests to bailout media companies if it failed to progress a law forcing digital platforms to pay local media for using their content. The advice suggested that "The government may come under pressure from news media entities to consider other more interventionist and costly options for supporting the news media industry, such as bailouts."

This advice suggested that the Fair Digital News Bargaining Bill might be the best mechanism to support a free and independent news media that is not reliant on government funding.

This exemplifies two of the ways in which the State is expected to provide for the media. Directly by means of a bailout or indirectly by means of providing the environment for continued funding in the form of compulsory subsidisation by large online platforms.

Both forms are interventionist. It is a matter of degree whether one is more interventionist than the other.

But the call for intervention comes from a number of quarters. Sir Ian Taylor made these comments recently.

“Since the news of the closure of Newshub, there has been a lot of commentary about this being an inevitable consequence of the changing viewership of media in general.

This is a landscape I think I have gathered some expertise in over the 34 years our company has been involved in international media.

Over that time I have watched our politicians, of all ilk, stand on the sideline while social media giants from overseas have pillaged the news stories researched and written by talented Kiwi journalists.

Off the back of this content, a new business model has devastated traditional media around the world.

A model where users are happy to give away their personal data for free to read stories these social media giants take for free, before selling that user data to advertisers, resulting in enormous profits, which our politicians then allow them to take offshore without paying tax.

It’s time our politicians "woke" to the reality that their failure to react to this changing landscape has allowed that change to happen, with no consequences at all. That’s if you don’t count the devastating news that those 300 Newshub staff and their families faced last week.”

This is just another variant of “the government must do something” theme but the real question is should there be State support for a model that is past its use by date. Sure, MSM plays an important part in our democratic processes – although given the quality of much of the content one must wonder how important – but there are other means in the digital paradigm for them to fulfil this role. The question is whether or not MSM are sufficiently aware of the potential of the Digital Paradigm and more important can focus on issues other than content in considering the means of doing business and delivering product to consumers.

A Look Into the Future

It may well be that the on-line convergence models utilised by MSM will not be around in 10 years time – and one need only look at the development of Social Media to understand the difference that Internet platforms may prompt in terms of behavioural norms and values. It may well be, for example, that MSM will fulfil a different news provision facility, focussing entirely upon factual information and stepping away from opinion and analysis, leaving that present function of MSM to citizen journalists – some of whom may be endorsed or who may write op-ed pieces on a freelance basis although it is acknowledged that this happens now.

A possible future is the fragmentation of MSM into a defined and specialist role – again enabled by the new technologies and possible future protocols that may ride on the backbone of the Internet – although it would require a culture shift for some journals to break free of a “tabloid” model and return to a more “intelligent” one.

The question that must be asked over and above the issue of the nature of content regulation is whether the model proposed is appropriate for the new technology. The basic model of control of “acceptable” content be it heresy, treason, pornography or other material injurious to the public good has not changed significantly since the Constitutions of Oxford 1407 which were designed to address the Lollard heresy. The model is labour intensive and has struggled to deal with increasing volumes of content made possible by technology. It was originally designed to censor manuscript materials. It struggled with the volume generated by print.

Perhaps societal changes and attitudes about indecent content have liberalised to the extent that a very limited definition of “objectionable” reduces the volume, but, having said that every film needs to be viewed and classified and the censors struggle under the volume of content that is contained in video games.

If we wish to maintain a content control model or a model that responds to content issues do we wish to maintain a variation of the existing model or should we consider adopting a new one. The current proposals suggest the former and, with the greatest respect, this seems to be a rear-view mirror approach to an upcoming and continuing problem. Rather than make behaviours driven by a new technology an uncomfortable fit with a model from a different paradigm, might it not be preferable to address the new paradigm and design a model that recognises it. This, of course, assumes that there is a justification for regulation in the first place. In this respect one looks at existing law and remedies.

It is acknowledged that current legal structures and processes make access to legal remedies and procedures difficult for the majority of the citizenry and are certainly not assisted by recent restrictions and cutbacks in legal aid. If the new paradigm continues or increases the occurrence of litigable behaviour then a new model needs to be developed to meet that. In this respect the Law Commission’s suggestion of a Communications Tribunal answered such a need.

This then leaves the issue of the special treatment accorded to MSM. Has the time has come, with the increased opportunities for “citizen journalism” to dispense with special treatment for MSM and make what have been privileges for MSM open to all? This may sound somewhat “Jeffersonian”, overly democratic or introducing an element of chaos into an otherwise reasonably ordered and moderately predictable environment. On the other hand in a world where everyone may be a publisher, a possible future is that MSM, at least as we recognise it now, may wither and either pass into history like the scribes in the monasteries or transform into some other form of information dissemination model.

Whilst acknowledging that the suggestion of making MSM privileges open to all is radical it must be remembered that the new paradigm with the various protocols that underlie Twitter, Instant Messaging, SMS and the various other models that will appear (and further change WILL come) radically alter our attitudes, approach to and expectations of information.

Edward Kennedy adapted the words of the Serpent in Shaw’s Back to Methuselah as an epitaph for his brother Robert F Kennedy “Some men see things as they are and say why? I dream things that never were and say why not?” In today’s age of democratisation, continued questioning and challenging of established systems and within an environment of dramatic innovation, New Media adherents may well ask “Why not?”

For MSM to have any credibility and respect they will need to have an answer. To say “it has always been this way” simply does not cut it in the digital paradigm because the opportunities that the paradigm offers means that it doesn’t have to be “this way”.

The answer lies in a true understanding of the medium.

[1] Keith Ng “MSD’s leaky Servers” Public Address On Point 14 October 2012 http://publicaddress.net/onpoint/msds-leaky-servers/ (last accessed 24 January 2017)

[2] Chris Keall “Keallhaulled” National Buisness Review On-line Edition 16 October 2012 https://www.nbr.co.nz/opinion/keith-ng-best-paid-journalist-new-zealand (last accessed 24 January 2017)

[3] Report 128 NZ Law Commission, Wellington March 2013

The issue with CBDCs (which of course is COMPLETELY ignored by the WEF's top-of-Google article about how wonderful they will be) is that in combination with advanced surveillance of where everyone is, what they buy, and (most scarily of all) what they SAY, online or anywhere else, CBCCs would make it splendidly easy for governments to exert complete control over their populace. All they would need to do is hook up the advanced surveillance system up to a personal social credit score as is already done in China. Then each (WEF controlled) national government could manipulate every individual person's ability to purchase... well, ANYTHING. Driven yr car too far this month? Your CBDC suddenly doesn't work at the gas station. Bought too much chocolate lately? The supermarket suddenly won't accept your CBDC for chocolate -- only for HEALTHY food like broccoli contaminated with glyphosate, or beer and wine (alcohol being thought by The Comptrollers to be good, (even though there's fairly good science saying it promotes cancer) because they reckon it keeps the plebs ever-so-slightly intoxicated and therefore less likely to complain -- note that liquor deliveries and grocery deliveries were never down during covid). OR, on a slightly larger scale, want to buy a new WASHING MACHINE? Sorry love, washing machines are off. Everybody rents household appliances now.

And golly gosh, suddenly national currencies disappear too, because the Comptrollers of the Currency for the entire world are now based in Switzerland. No problem with exchange rates now. We have a World Government now -- everyone is a citizen of the world.

Oh Brave New World, that has such money in it.

https://consultations.rbnz.govt.nz/money-and-cash/digital-cash-in-new-zealand/

Lots of assurances, but how long will they last? And what a surprise, it's happening all over the world, at the same time. Ask Google about "Global push for CBDCs" ....